|

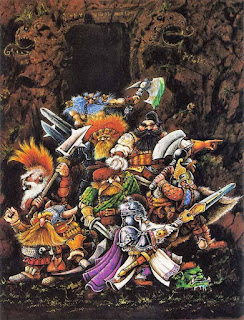

| Dwarrowdeep has Good Art |

I don’t know Greg Gillespie, I don’t have any intense feeling for his work or his design history, as while I have looked at some of previous adventures they haven’t made much impression on me. I suspect he was on G+ and I may have spoken to him there, but I don’t remember anything specific from those long ago days. I purchased the Dwarrowdeep PDF (which costs as much as a good bottle of booze or nice steak - but cost isn’t a criteria I use to judge adventures) specifically to read it for this review and because of my overall interest in megadungeon design. I have not played it and don’t intend to. As always I will take a look at it for what it offers as a playable product and from my perspective as someone interested in dungeon and megadungeon design. I feel somewhat guilty about this review and don’t expect Mr. Gillespie will appreciate it much, but after spending a week reading Dwarrowdeep - time I could have used for paying work or on my own hobby projects - I can't play nice for the sake of comity, even if I'm not trying to be cruel. Darrowdeep is an abject failure, but in that offers a useful example of how not to design a megadungeon and asks questions about the limits of dungeon design.

Dwarrowdeep is the new (May 2022) 336 page megadungeon by Greg Gillespie, known as the writer of Barrowmaze and a few other big dungeons. This has made Gillespie a notable figure and dungeon designer from the early and middle years of the OSR. What Dwarrowdeep offers is a brand new megadungeon that I had hopes would highlighting the state of design in 2022 and the evolution of the form since the early days of the OSR or at least the 2010’s when Gillespie published Barrowmaze ... if it does, it only shows a loss of basic knowledge and the decline of OSR design and imagination over the past decade.

In light of its recent publication and Gillespie’s long career as a megadungeon designer I was hopeful that Dwarrowdeep would be something special, offering new ideas, or better utility - in short I was hopeful that it might have something to teach about megadungeon design. I was gravely disappointed. When I write reviews I try to be charitable and understand the author's goals rather than focus only on the work's failings, but Dwarrowdeep’s positive aspects are largely limited to the excellent art within, an audacious scope, and occasional moments when a decent idea shines through the mediocrity.

Dwarrowdeep fails as a megadungeon in three interrelated and key ways: variety, interactivity, and usability. I suspect this is the result of both ambitiously excessive scope and the poisonous idea that nostalgia alone is sufficient to produce good work. What I mean is that Dwarrowdeep doesn’t just try to provide a nostalgic aesthetic or feel, it goes deeper, with nostalgic layout choices, nostalgic key design, and nostalgic approach to setting (generally emulating the early 1980’s BECMI era TSR adventures). This fails, partially on its own merits, but partially because it’s so insistent on cleverly aping a particular, possibly imaginary, past that it ignore the work of other designers, both since the early 80’s and before. Dwarrowdeep drowns because it chooses to submerge itself in the nostalgia for a design that wasn't optimal even for the 30-page BECMI modules where it first appeared.

WHAT IS A DWARROWDEEP?

Dwarrowdeep begins by making the claim that it is “the largest dwarven-themed sandbox dungeon ever created”. It’s likely right, at least among published RPG products. The first thing I know that comes close is the 1993 TSR boxed set “Dragon Mountain'' which might also be described as a “the largest kobold-themed adventure path and sandbox dungeon ever created”; so I can’t quibble with Dwarrowdeep’s claims about scope. Another option might be the 1984 Middle Earth Role Playing "Moria - The Dwarven City", which uses far better design principles including Stonehell style one page regions and has very good maps - but is only 75 pages (the 1994 edition is 175 pages but that's down to the wordy style of the mid 90's) and is mostly inspirational reading. Dwarrowdeep is almost certianly the biggest faux-Moria ever published.

Dwarrowdeep isn't just dungoen, it contains a town, region, and that ruined dwarven city in the style of Tolkien’s Mines of Moria. In two important ways it fails all of these possible predecessors, it lacks the mood and intensity of Tolkien, despite slavish emulation (understandable), but also it fails to provide the basic elements of a functional megadungeon or even the clumsy utility of Dragon Mountain (incomprehensible). Dwarrowdeep bites off more than its author’s imagination can chew. The least of Dwarrowdeep’s problems is that it's dripping with cliche - while this annoys me, so many players love fantasy cliche so I won't even claim this is an issue for its aesthetics. Vanilla or vernacular fantasy is a helpful and standard practice (though Anomalous Subsurface Environment proves it's not necessary) in megadungeon design because using a world where the implied setting of the rulebooks and the genre expectations of most players and referees can easily fill in blanks dramatically helps to shorten keys and streamline the overall adventure. Unfortunately Dwarrowdeep’s other design issues mean that it can’t or doesn’t take advantage of its choice to use the an exceptionally trite version of the lost dwarfhold cliche. It also errs in extending cliches to its physical design and mechanics -- which is a huge mistake for a work that isn't really a classic keyed megadungeon.

|

| The City Stealing Kind of Dwarf |

IT'S GOT DWARF THINGS

So at first glance Dwarrowdeep is very much a classic megadungeon, set on its regional map and designed to enable an “extended campaign lasting months or years” that rarely leaves the megadungeon. Surprisingly, it isn't a “world dungeon” -- a setting where there is only the megadungeon with no overworld -- and lacking that pretense it very much risks being quickly set aside for adventures on the regional map. Even with less tedious megadungeons, players often decide to venture into the wider world for various reasons. With Dwarrowodeep this danger is much greater as its contents are so monotonous I can’t see any party (no matter how enthused by dwarves and Gygaxian fantasy) bothering with the dungeon for more than a few sessions. Finally, however classic or standard Darrowdeep’s physical design, it takes tentative steps towards the currently popular method of using procedural generation to fill in large areas of the dungeon map.

This isn’t to say it’s a “depth crawl” or a toolkit, it's procedural generation mostly uses techniques drawn from Gygax's D1 - Descent into the Depths of the Earth. Darrowdeep is a megadungeon in the early OSR style, akin to Stonehell, but far less innovative or enjoyable. 151 of Dwarrowdeep’s 233 page are keyed dungeon locations, densely packed onto two column pages in an unbroken torrent of mostly minimalist dungeon keys. Even with hundreds of keys, the majority of the dungeon Dwarrowdeep presents is unkeyed. Miles of passages are traversed using a system again drawn from Gygax’s Descent into the Depths of the Earth: randomly generated obstacles and encounters at a near wilderness travel scale that link the dungeon's few key regions and a larger number of geomorphic nodes that the referee must populate from a dozen or so random tables.

The content of the dungeon is precisely what anyone familiar with Moria would expect: assorted evil humanoids forted up in a ruined dwarven city of mines, tombs, defenses, and forges. There is some variation, and occasional glimpses of enjoyable novelty, but in general Dwarrowdeep remains aggressively nostalgic, supremely repetitive, locked into a vision of fantasy that is constrained, conservative in its aesthetics, and stifles design, usability, and playability. It's not the cliched nature of these locations that make them bland, its a larger lack of variation. There are no overgrown fungus caverns, giant crumbling machines, towering apartment blocks, vast quarries, or flooded ore docks on the edge of underground seas -- only tightly packed, often largely symmetrical dwarf halls and fortresses with almost no elevation differences and winding mines or caverns of 10' passages. Variety is key to a megadungeon, and there's very little in Dwarrowdeep.

IT'S HUGE

The scope of Dwarrowdeep is its most notable aspect, an adventure with hundreds of pages of keys for large regions or nodes (many areas are over 100 keys), but Dwarrowdeep is so enormous that these spaces make up a relatively small portion of the mountain. Like Tolkien's Moria, Dwarrowdeep is largely empty. In what seems a poor choice, rather than creating a set of subsystems for moving quickly through its abandoned spaces, Dwarrowdeep choses to procedurally generate them. This choice seems especially odd given Dwarrowdeep’s enormous, impossible scope, because it falls short both in of the limited variety of content on the generation tables and because the idea of spending most of a campaign navigating empty and vaguely described spaces is singularly unappealing. I don't think the solution is simply a bigger set of keys - 900 pages of keyed Dwarrowdeep would add little and it’s perhaps a mercy that the Geomorphs and procedural generation are instead asked to do a great deal of work (though with them so is the referee).

All this makes the functionality, variety, and appeal of this likely necessary procedural generation a special concern. Parties will spend days of travel (at an unclear exploration scale on an undergorund hex map) between its keyed nodes on paths that generally pass through multiple geomorph generated spaces requiring room by room exploration. Campaign players will interact with the randomized contents of a few tables at the back of Dwarrowdeep far more often and for many more hours of play than they do with the keyed locations.

IT'S PRETTY

As weak as its mechanics and keys sometimes are, and I’ll take more time to look at them below, Dwarrowdeep is a polished product with workmanlike overall production, editing, and writing. Despite some emphasis on the currently popular practice of procedural dungeon generation, Dwarrowdeep’s production as well as its aesthetics, setting, and theme all feel extremely nostalgic. Considering this though, it’s very nicely produced for its chosen design style, a reminder of how far expectations for RPG layout and especially cartography (thanks Dyson) have come in the past ten years. Dwarrowdeep has solid, slightly stodgy, overall design that while not especially notable or remotely innovative … is a shockingly and obviously more attractive product than TSR’s box set “Dragon Mountain” (1993), which I noted above as Dwarrowdeep’s clear TSR predecessor and which was made by a larger team with the backing of a large publisher.

Dwarrowdeep’s overall production and design is pleasantly competent for higher quality indie RPGs in 2022, though its PDF lacks usability tools such as links and its organization choices are far from ideal. Dwarrowdeep's art however is of very high quality and very generous, with almost every page containing at least a few flourishes. While, like the rest of the adventure, the art tends towards predictable and generic fantasy images, it’s often extremely imaginative within those constraints. There are numerous artists, with many well known TSR-era illustrators providing at least a few pieces. Their professionalism and long association with fantasy art shows through.

In contrast to many large works with numerous artists Dwarrowdeep's art is rarely jarring, despite distinctive styles the overall quality of the pieces and the welcome limitations of black and white line means the work all comes together with a sort of classic fantasy RPG art sensibility. The art has a similar charm to the original Dungeon Master's Guide, and the single most enjoyable part of reading it for this review was seeing what the (consistent and provided as pregens) party of adventurers depicted on most pages would get into next. Dwarrowdeeps best art is much higher quality then these little vignettes, as the regional overview includes a full page piece by Darlene: a densely and finely inked woodland that feels fantastical because of its precise, crisp illustration and detail rather than its specific content. Darlene manages to evoke art nouveau illustration without being an obvious copy of any one artist. Equally impressive are a set of wonderful, often full page, illustrations of empty spaces within the ruined dwarf home: vast halls, crumbling lines of columns, vertiginous stairways, and bone scattered catacombs. All of these are done in bleak, heavily shadowed style and drawn with a real attention to line weight and use of negative spaces. These illustrations are at times nearly architectural, but also have a strong feel of Pirenesi’s Caceri — and like the 16th century prints, represent an inspiring creation of monumental fantastic space through perspective and line.

Sadly art alone isn’t the adventure, and alone can’t make thousands of very similar locations, poor usability, random generation tools insufficient for the adventure’s scale, or a toxic level of nostalgia into a functional adventure.

|

| Dwarrowdeep's Best Art Isn't Available Online. This Cyclopsman is still good |

DURIN’S LAMENT

I can’t think of a good dwarven ruin-themed megadungeon, despite the importance of the Mines of Moria to the concept of the RPG dungeon (which is not a prison). The only one that comes to mind is the 1993 2nd edition TSR box set “Dragon Mountain”, which while well reviewed at the time, is a product of the post - Dragonlance era of TSR design -- meaning it is largely an adventure path and has not retained its popularity. This suggests that the ambition behind Dwarrowdeep isn’t entirely misplaced, it’s a creation aimed squarely at one of the principle literary sources of the “dungeon” and one that hasn’t been addressed in a definitive way. One struggle is to see how Dwarrowdeep’s somewhat glib embrace of the foundational dungeon cliche -- a generalized application of the themes and tropes of the dwarven ruin, could make for something more memorable than Dragon Mountain, let alone Moria.

Comparing Dwarrowdeep to its most obvious aesthetic source, Tolkien’s description of Moria, is illustrative. The Fellowship of the Ring’s Moria is a series of disjointed scenes, which works well as a fictional device to capture the discombobulation, vastness, and ominous threat of a 40 mile trip through a pitch black, demon haunted ruin. Obviously this sort of technique doesn’t make for good classic dungeon design. First, despite its impact, Tolkien’s Moria is minimally described. All the reader learns of know of it are its magic door, branching tunnels, an ominous deep well, rusty chains, flooded halls below, a great hall for Gimili’s lament, Balin’s tomb, and the Bridge of Khazad-dum. A dungeon crawl needs to allow for exploring a fantastical space, not just provide a few evocative images.

I can’t think of a good dwarven ruin-themed megadungeon, despite the importance of the Mines of Moria to the concept of the RPG dungeon (which is not a prison). The only one that comes to mind is the 1993 2nd edition TSR box set “Dragon Mountain”, which while well reviewed at the time, is a product of the post - Dragonlance era of TSR design -- meaning it is largely an adventure path and has not retained its popularity. This suggests that the ambition behind Dwarrowdeep isn’t entirely misplaced, it’s a creation aimed squarely at one of the principle literary sources of the “dungeon” and one that hasn’t been addressed in a definitive way. One struggle is to see how Dwarrowdeep’s somewhat glib embrace of the foundational dungeon cliche -- a generalized application of the themes and tropes of the dwarven ruin, could make for something more memorable than Dragon Mountain, let alone Moria.

Comparing Dwarrowdeep to its most obvious aesthetic source, Tolkien’s description of Moria, is illustrative. The Fellowship of the Ring’s Moria is a series of disjointed scenes, which works well as a fictional device to capture the discombobulation, vastness, and ominous threat of a 40 mile trip through a pitch black, demon haunted ruin. Obviously this sort of technique doesn’t make for good classic dungeon design. First, despite its impact, Tolkien’s Moria is minimally described. All the reader learns of know of it are its magic door, branching tunnels, an ominous deep well, rusty chains, flooded halls below, a great hall for Gimili’s lament, Balin’s tomb, and the Bridge of Khazad-dum. A dungeon crawl needs to allow for exploring a fantastical space, not just provide a few evocative images.

Second, most of the power of the two chapters that document Moria come from the stories that the fellowship tells or discovers about the place. Tolkien He spends as much time describing an orc chief that stabs Frodo as he does on Moria’s great hall of pillars and glassy black walls. Instead we get song and metaphor as well as the grim account of Balin’s failed expedition. It’s all powerful stuff for fiction, building threat and oppressive darkness -- but again dungeon crawling RPG adventures aren’t about using scenes to tell a story and characterization (Gandalf’s obvious fear, Boromir’s foolish and ineffectual bravery, Gimili moved to poetry by sadness, or Pippin’s realization that his shenanigans threaten horrific consequences) to create an emotional response. RPG dungeon crawls are a game of navigating fictional space through interacting with the referee's (and designer’s) clear description. Tolkien may offer a set of feelings and a few pithy descriptions - but it's up to Greg Gillespie to turn them into usable adventure content.

Instead, the focus on fictional Moria makes Dwarrowdeep stumble as a usable adventure. Tolkien’s Moria is a journey through an enormous and largely abandoned ruin. The Fellowships sneaks through the dark above the flooded, orc infested, and Balrog ruled halls below. Tolkien’s journey is a series of scenes, impressions, and fragments that use the vast empty darkness and the power of the novel to skip or compress most of the dungeon into a few words without concern that the novel’s characters will want to investigate something or wander the wrong direction. This doesn’t work in a classic dungeon crawl, at least not without significant mechanics for faster travel through empty halls.

As a referee you have a few hours to play a game about exploring a location, discovering its secrets and interacting with its inhabitants, but you lack a novelist’s tools to skip time and direct exploration. Turnkeeping, navigation, and player choice are primary elements of classic dungeon adventures and they often work against narrative story-telling. For a Contemporary Traditional game where exploration and navigation are a function of a few stat checks, one could follow Tolkien’s concept of Moria as an empty vastness, and even his narrative structure, more directly. 5E design allows for a series of exciting scenes linked by quick referee narratives because it mostly depends on set-piece combat encounters where 5E’s player choice largely occurs. Since this understanding of play is not a part of the classic dungeon crawl, certainly not as Dwarrowdeep understands it, silent and empty halls stretching for days beneath the mountain offer only monotony not Tolkien's forbidding.

THE MONOTONY OF DWARROWDEEP

The gameable content of Dwarrowdeep is no more novel than its overall theme. At the start Dwarrowdeep's introduction certainly isn’t memorable or inspiring, but at least it’s only six pages.

“The/some/these Dwarves were chased from their mountain city by exiled bad dwarves”. Presumably this makes them different than their neighbors who suffered a balrog infestation, or was it a dragon - dwarves are irresponsible property owners. Now they want it back. They don’t have the army to take it. They will have to depend on heavily armed tomb robbers and desperadoes… That’s your overall hook.

There is some history, but it doesn’t matter much; it’s certainly neither complex or unexpected enough to act as the basis of puzzles and secrets in the larger adventure: it's the opposite of what we see in Tolkien’s poetic descriptions of Moria and something that is generally quite important to maintaining freshness in a megadungeon. Otherwise Dwarrowdeep’s regional setting has everything one would expect from Northern European based generic fantasy that clings closely to Gygax and Tolkien's pants legs. The ‘Deep’ is located in a feudal type pocket polity surrounded by mountains and beset by humanoid raiders. Knights are implied, merchants mentioned, there’s a free city, and a land full of battle sites, ruined forts, and trade routes. Everything is of strategic importance and/or relates to some past conflict - though most aren’t especially important to the megadungeon itself. They are perfectly acceptable as a small fantasy region, but also deeply and sadly predictable. I will dub these lands the “Dells of Lost Opportunity” Dwarrowdeep calls them something less memorable.

I tend to be snide about this sort of standard Gygaxian vernacular fantasy setting, and where Dwarrowdeep deviates from cliche it does manage to offer something moderately memorable, such as its band of otherworldly cyclops led by a blind cleric who can travel between megalithic stone circles. This is an interesting piece of regional world building, offering a race of potential characters, a regional faction and a means of ‘fast travel’ to discover. There are few other aspects of interesting subversion or transformation of the obvious cliches, but overall Dwarrowdeep is bland and more disappointing. Its overworld factions, even when theoretically attached to the megadungeon (the dwarven exiles), don't have much in the way of specific connections or goals.

Again this first section or impression is typical of almost every aspect of Dwarrowdeep, it manages to include interesting or useful elements but just leaves them floating, without support or connection to the adventure — marooned in a sea of dwarf based cliches. Remember how I mentioned Tolkien’s Moria is described in two short chapters, maybe a 100th the length of Dwarrowdeep? Yet, while the literary Moria lacks physical description, architecture, or design, it still contains plots, secrets, and stories. Most are implied and unanswered in Tolkien, for example Durin’s crown lost in the flooded deeps, one star among a subterranean nebula of jewels (or eyes), sounds like the basis of an adventure hook. If only some dwarf followed Gimili’s example and related this mystery to the characters in Dwarrowdeep. The story of a powerful lost artifact has potential.

Dwarrowdeep may even have a lost magic artifact, but there are no such allegorical rumors in Dwarrowdeep, and this is where one begins to notice that the generic nature of the adventure is less an issue than the fact that this blandness is piled high to conceal a lack of basic coherence and the complexity necessary for a megadungeon. I may dislike generic fantasy settings, and they do produce problems because they reduce player engagement and must adhere to player expectations to avoid feeling unfair, but even the most generic of settings can still use hooks, rumors, and NPCs effectively.

“But still the sunken stars appear

In dark and windless Mirrormere;

There lies his crown in water deep,

Till Durin wakes again from sleep.”

This is the last line of “The Song of Durin” that I’ve been talking about, the lament Gimili sings when the Fellowship enters the black mirror polished great hall of Moria. It’s a damn effective rumor.

“The Eternal Mountains are known as Thaneduhr’s Throne to the dwarves.”

This is a rumor in Dwarrowdeep. I’m not going to demand that RPG rumors have the poetics of Tolkien, but the verse offers more usable, gameable content than the Dwarrowdeep rumor. Give the players the name of a location within the dungeon “Mirrormere”, a magic crown and vague implication that its recovery will awaken a slumbering Demi-god. Don’t tell them a random useless factoid. Dwarrowdeep's rumor is especially infuriating because it is one of exactly seven rumors (on a table of 20) that relate even tangentially to a 1,000 key megadungeon and none mention the lost artifact. Nor do any of the NPCs offered provide much in the way of hooks.

There is no need for this sort of cursory, blithe design - it’s not as if Dwarrowdeep lacks the page length to offer decent rumors or functional hooks, it’s that a conscious choice has been made to spend about ten pages on Dwarf lore and town description but provide almost nothing playable or inspiring: Dwarves value their beards, they like drinking, they use runes and have Scots accents, they honor clan and family etc. One wonders, what's the purpose of pages of vernacular fantasy pastiche, especially if it lacks directly gameable content, and why offer it instead of actionable hooks and rumors? This is the real problem with Dwarrowdeep’s nostalgic aesthetic, it’s not used to fit more content into a smaller space, but rather to pad space because there’s not enough creative content to match the adventure’s pretense of scope.

Instead, the focus on fictional Moria makes Dwarrowdeep stumble as a usable adventure. Tolkien’s Moria is a journey through an enormous and largely abandoned ruin. The Fellowships sneaks through the dark above the flooded, orc infested, and Balrog ruled halls below. Tolkien’s journey is a series of scenes, impressions, and fragments that use the vast empty darkness and the power of the novel to skip or compress most of the dungeon into a few words without concern that the novel’s characters will want to investigate something or wander the wrong direction. This doesn’t work in a classic dungeon crawl, at least not without significant mechanics for faster travel through empty halls.

As a referee you have a few hours to play a game about exploring a location, discovering its secrets and interacting with its inhabitants, but you lack a novelist’s tools to skip time and direct exploration. Turnkeeping, navigation, and player choice are primary elements of classic dungeon adventures and they often work against narrative story-telling. For a Contemporary Traditional game where exploration and navigation are a function of a few stat checks, one could follow Tolkien’s concept of Moria as an empty vastness, and even his narrative structure, more directly. 5E design allows for a series of exciting scenes linked by quick referee narratives because it mostly depends on set-piece combat encounters where 5E’s player choice largely occurs. Since this understanding of play is not a part of the classic dungeon crawl, certainly not as Dwarrowdeep understands it, silent and empty halls stretching for days beneath the mountain offer only monotony not Tolkien's forbidding.

THE MONOTONY OF DWARROWDEEP

The gameable content of Dwarrowdeep is no more novel than its overall theme. At the start Dwarrowdeep's introduction certainly isn’t memorable or inspiring, but at least it’s only six pages.

“The/some/these Dwarves were chased from their mountain city by exiled bad dwarves”. Presumably this makes them different than their neighbors who suffered a balrog infestation, or was it a dragon - dwarves are irresponsible property owners. Now they want it back. They don’t have the army to take it. They will have to depend on heavily armed tomb robbers and desperadoes… That’s your overall hook.

There is some history, but it doesn’t matter much; it’s certainly neither complex or unexpected enough to act as the basis of puzzles and secrets in the larger adventure: it's the opposite of what we see in Tolkien’s poetic descriptions of Moria and something that is generally quite important to maintaining freshness in a megadungeon. Otherwise Dwarrowdeep’s regional setting has everything one would expect from Northern European based generic fantasy that clings closely to Gygax and Tolkien's pants legs. The ‘Deep’ is located in a feudal type pocket polity surrounded by mountains and beset by humanoid raiders. Knights are implied, merchants mentioned, there’s a free city, and a land full of battle sites, ruined forts, and trade routes. Everything is of strategic importance and/or relates to some past conflict - though most aren’t especially important to the megadungeon itself. They are perfectly acceptable as a small fantasy region, but also deeply and sadly predictable. I will dub these lands the “Dells of Lost Opportunity” Dwarrowdeep calls them something less memorable.

I tend to be snide about this sort of standard Gygaxian vernacular fantasy setting, and where Dwarrowdeep deviates from cliche it does manage to offer something moderately memorable, such as its band of otherworldly cyclops led by a blind cleric who can travel between megalithic stone circles. This is an interesting piece of regional world building, offering a race of potential characters, a regional faction and a means of ‘fast travel’ to discover. There are few other aspects of interesting subversion or transformation of the obvious cliches, but overall Dwarrowdeep is bland and more disappointing. Its overworld factions, even when theoretically attached to the megadungeon (the dwarven exiles), don't have much in the way of specific connections or goals.

Again this first section or impression is typical of almost every aspect of Dwarrowdeep, it manages to include interesting or useful elements but just leaves them floating, without support or connection to the adventure — marooned in a sea of dwarf based cliches. Remember how I mentioned Tolkien’s Moria is described in two short chapters, maybe a 100th the length of Dwarrowdeep? Yet, while the literary Moria lacks physical description, architecture, or design, it still contains plots, secrets, and stories. Most are implied and unanswered in Tolkien, for example Durin’s crown lost in the flooded deeps, one star among a subterranean nebula of jewels (or eyes), sounds like the basis of an adventure hook. If only some dwarf followed Gimili’s example and related this mystery to the characters in Dwarrowdeep. The story of a powerful lost artifact has potential.

Dwarrowdeep may even have a lost magic artifact, but there are no such allegorical rumors in Dwarrowdeep, and this is where one begins to notice that the generic nature of the adventure is less an issue than the fact that this blandness is piled high to conceal a lack of basic coherence and the complexity necessary for a megadungeon. I may dislike generic fantasy settings, and they do produce problems because they reduce player engagement and must adhere to player expectations to avoid feeling unfair, but even the most generic of settings can still use hooks, rumors, and NPCs effectively.

“But still the sunken stars appear

In dark and windless Mirrormere;

There lies his crown in water deep,

Till Durin wakes again from sleep.”

This is the last line of “The Song of Durin” that I’ve been talking about, the lament Gimili sings when the Fellowship enters the black mirror polished great hall of Moria. It’s a damn effective rumor.

“The Eternal Mountains are known as Thaneduhr’s Throne to the dwarves.”

This is a rumor in Dwarrowdeep. I’m not going to demand that RPG rumors have the poetics of Tolkien, but the verse offers more usable, gameable content than the Dwarrowdeep rumor. Give the players the name of a location within the dungeon “Mirrormere”, a magic crown and vague implication that its recovery will awaken a slumbering Demi-god. Don’t tell them a random useless factoid. Dwarrowdeep's rumor is especially infuriating because it is one of exactly seven rumors (on a table of 20) that relate even tangentially to a 1,000 key megadungeon and none mention the lost artifact. Nor do any of the NPCs offered provide much in the way of hooks.

There is no need for this sort of cursory, blithe design - it’s not as if Dwarrowdeep lacks the page length to offer decent rumors or functional hooks, it’s that a conscious choice has been made to spend about ten pages on Dwarf lore and town description but provide almost nothing playable or inspiring: Dwarves value their beards, they like drinking, they use runes and have Scots accents, they honor clan and family etc. One wonders, what's the purpose of pages of vernacular fantasy pastiche, especially if it lacks directly gameable content, and why offer it instead of actionable hooks and rumors? This is the real problem with Dwarrowdeep’s nostalgic aesthetic, it’s not used to fit more content into a smaller space, but rather to pad space because there’s not enough creative content to match the adventure’s pretense of scope.

|

| John Blanche Drew These Dwarves in 1985. They have flavor. |

There is minimal variation, a frozen tower entrance high in the mountains that is the lair of a powerful white dragon. For the most part though, even once the party delves deep into the earth, Dwarrowdeep’s keyed areas consist of humanoid outposts and lairs: orcs, stronger black orcs, derro, kuo-toa, and dark dwarves. In each, themes repeat in unimaginative ways - guard rooms, and ruined temples, rooms with rot grub infested corpses whose stench causes vomiting, false tombs and slightly better hidden true tombs of various dwarven heroes clutching magic weapons and piled runestones which contain meaningless inscriptions. Little changes between these locations except the complexion and size of the evil not-people one is fighting. Again, Dwarrowdeep is huge, the entire dungeon might be a five year campaign from levels 1 to 10. It would be an excruciating one, something close to playing one of the “gold box” Dungeons & Dragons videogames of the 90’s where every area was a series of barely distinguishable corridors and intermittent combat encounters. This moves beyond simply a bland aesthetic into the larger issues that Dwarrowdeep has - even where it’s keyed and mapped it’s not designed as a useful megadungeon.

FAILURES OF DUNGEONEERING

What makes a decent megadungeon? There are a number of answers to this: maps, levels, hundreds of keys … reading through years of attempts though I think megadungeons work when they can hold interest over many sessions. What’s the point of a huge dungeon if the players refuse to continue adventuring in it after a few weeks?

Comparing Dwarrowdeep to the best (almost) megadungeon I’ve reviewed here: Caverns of Thracia, it’s obvious that it contains several things that Dwarrowdeep profoundly lacks, despite Dwarrowdeep’s far grander scale. Variation, secrets, and faction Intrigue. There’s only so many rooms of fallen stones, orc outposts, and dwarf skeletons that a party can explore. Reading through Dwarrowdeep it’s clear that nostalgic embrace of aesthetic or setting alone is insufficient for Dwarrowdeep’s scope - technique is needed.

This is why attempting to emulate the feel of Tolkien’s Moria without access to the novelist’s tools creates grave problems. Beyond an unconsidered embrace of Tolkien, a greater failure of Dwarrowdeep’s design is that it seems to refuse or reject the idea it must replace Fellowship of the Ring’s narrative tools with something appropriate to its medium and play style. Instead, Dwarrowdeep doubles down on nostalgia -- not only as setting and aesthetic, but in its adventure design. Nostalgia has risks, it elevates the design or methods of the past in search of an idealized feeling or representation of memory. Part of nostalgia becoming more than a personal inspiration is a claim that artifacts or representations of the past actually represent the nostalgic ideal. If you insist something from the 1940’s is the perfect fantasy story or an adventure from 1982 the perfect dungeon design, you can’t change, adapt or modernize. Nostalgia, once it becomes ideological instead of a personal memory, traps the nostalgic. Worse is the way this sort of nostalgic worship of an iconic work of image prevents deep examination of that past. Once we declare something the ideal, other lines of thought and products of the same era must be ignored where they contradict or offer alternatives. Dwarrowdeep is trapped. Being trapped in recreating Moria might be great - Tolkien’s two chapters are quite inspirational still, but being trapped in trying to do this with the design choices of BECMI is a disaster.

Dwarrowdeep can’t or hasn’t learned the lessons that even Dragon Mountain has about megadungeon design. It’s firmly rooted in the design of early 1980’s TSR, just the time when the free form and experimentation of Gygax and other original designers began to drain away, but before the tyranny of the storypath became entirely dominant. Dwarrowdeep’s keying and structure greatly resemble an adventure like Horror on the Hill, or perhaps the drudgery of King’s Festival minus the box text. In picking this moment of dungeon design to emulate, Dwarrowdeep largely refuses to learn from either the earliest adventures, or the adventures such as Stonehell or Anomalous Subsurface Environment that were produced later by the OSR. Dwarrowdeep isn’t entirely limited to this design period, and Gillespie occasionally escapes from its gravity, especially when he attempts to apply the underdark travel of Gygax’s D series, but the keying style and adventure sensibilities of Mid-TSR remain dominant and detrimental

To put it another way, both Lost Caverns of Thracia and Stonehell are far more innovative than Dwarrowdeep, because they make informed and inspired attempts to produce a playable megadungeon rather than what seem like empty gestures in the direction of a megadungeon. A project of Dwarrowdeep’s scope is unlikely to succeed everywhere, but putting aside its excellent art it’s fascinating that Dwarrowdeep succeeds almost nowhere -- and largely to the degree that it cautiously apes the mechanics and style of past works. As a dungeon Dwarrowdeep fails to provide faction intrigue, useful keying, or the sorts of mysteries and larger secrets that would justify considering it for a long campaign.

FACTION INTRIGUE

The first and best way to maintain interest and challenge in a large or small dungeon environment is to offer memorable factions and NPCs. I don’t mean using funny voices, but including groups and powerful individuals in the dungeon whose interests align partially with the party and who are open to interaction other than combat. Dwarrowdeep notes that it contains “Two factions, very broadly defined”. The Duergar and their massive alliance of: orc, black orc, derro, kuo-toa, and trolls make up the major faction while the other consists of a few scattered individuals such as the white dragon and small groups like a pack of gem mining Xorns, or randomly encountered fungus people and troglodytes. The iproblem is that none of these lesser "factions" make for much in the way of allies against the overwhelming (and monotonously keyed) might of the duergar. The large number of foes in Dwarrowdeep mean that not only will battles be frequent, but they will be large and very time consuming. The non-allied groups are too small to matter much and ones that could be useful such as the dragon or Xorn aren’t provided with any sort of relationships or goals that would allow players to negotiate with them meaningfully. The party will be fighting these battles alone, regardless of who one characterizes the "factions" in Dwarrowdeep.

FAILURES OF DUNGEONEERING

What makes a decent megadungeon? There are a number of answers to this: maps, levels, hundreds of keys … reading through years of attempts though I think megadungeons work when they can hold interest over many sessions. What’s the point of a huge dungeon if the players refuse to continue adventuring in it after a few weeks?

Comparing Dwarrowdeep to the best (almost) megadungeon I’ve reviewed here: Caverns of Thracia, it’s obvious that it contains several things that Dwarrowdeep profoundly lacks, despite Dwarrowdeep’s far grander scale. Variation, secrets, and faction Intrigue. There’s only so many rooms of fallen stones, orc outposts, and dwarf skeletons that a party can explore. Reading through Dwarrowdeep it’s clear that nostalgic embrace of aesthetic or setting alone is insufficient for Dwarrowdeep’s scope - technique is needed.

This is why attempting to emulate the feel of Tolkien’s Moria without access to the novelist’s tools creates grave problems. Beyond an unconsidered embrace of Tolkien, a greater failure of Dwarrowdeep’s design is that it seems to refuse or reject the idea it must replace Fellowship of the Ring’s narrative tools with something appropriate to its medium and play style. Instead, Dwarrowdeep doubles down on nostalgia -- not only as setting and aesthetic, but in its adventure design. Nostalgia has risks, it elevates the design or methods of the past in search of an idealized feeling or representation of memory. Part of nostalgia becoming more than a personal inspiration is a claim that artifacts or representations of the past actually represent the nostalgic ideal. If you insist something from the 1940’s is the perfect fantasy story or an adventure from 1982 the perfect dungeon design, you can’t change, adapt or modernize. Nostalgia, once it becomes ideological instead of a personal memory, traps the nostalgic. Worse is the way this sort of nostalgic worship of an iconic work of image prevents deep examination of that past. Once we declare something the ideal, other lines of thought and products of the same era must be ignored where they contradict or offer alternatives. Dwarrowdeep is trapped. Being trapped in recreating Moria might be great - Tolkien’s two chapters are quite inspirational still, but being trapped in trying to do this with the design choices of BECMI is a disaster.

Dwarrowdeep can’t or hasn’t learned the lessons that even Dragon Mountain has about megadungeon design. It’s firmly rooted in the design of early 1980’s TSR, just the time when the free form and experimentation of Gygax and other original designers began to drain away, but before the tyranny of the storypath became entirely dominant. Dwarrowdeep’s keying and structure greatly resemble an adventure like Horror on the Hill, or perhaps the drudgery of King’s Festival minus the box text. In picking this moment of dungeon design to emulate, Dwarrowdeep largely refuses to learn from either the earliest adventures, or the adventures such as Stonehell or Anomalous Subsurface Environment that were produced later by the OSR. Dwarrowdeep isn’t entirely limited to this design period, and Gillespie occasionally escapes from its gravity, especially when he attempts to apply the underdark travel of Gygax’s D series, but the keying style and adventure sensibilities of Mid-TSR remain dominant and detrimental

To put it another way, both Lost Caverns of Thracia and Stonehell are far more innovative than Dwarrowdeep, because they make informed and inspired attempts to produce a playable megadungeon rather than what seem like empty gestures in the direction of a megadungeon. A project of Dwarrowdeep’s scope is unlikely to succeed everywhere, but putting aside its excellent art it’s fascinating that Dwarrowdeep succeeds almost nowhere -- and largely to the degree that it cautiously apes the mechanics and style of past works. As a dungeon Dwarrowdeep fails to provide faction intrigue, useful keying, or the sorts of mysteries and larger secrets that would justify considering it for a long campaign.

FACTION INTRIGUE

The first and best way to maintain interest and challenge in a large or small dungeon environment is to offer memorable factions and NPCs. I don’t mean using funny voices, but including groups and powerful individuals in the dungeon whose interests align partially with the party and who are open to interaction other than combat. Dwarrowdeep notes that it contains “Two factions, very broadly defined”. The Duergar and their massive alliance of: orc, black orc, derro, kuo-toa, and trolls make up the major faction while the other consists of a few scattered individuals such as the white dragon and small groups like a pack of gem mining Xorns, or randomly encountered fungus people and troglodytes. The iproblem is that none of these lesser "factions" make for much in the way of allies against the overwhelming (and monotonously keyed) might of the duergar. The large number of foes in Dwarrowdeep mean that not only will battles be frequent, but they will be large and very time consuming. The non-allied groups are too small to matter much and ones that could be useful such as the dragon or Xorn aren’t provided with any sort of relationships or goals that would allow players to negotiate with them meaningfully. The party will be fighting these battles alone, regardless of who one characterizes the "factions" in Dwarrowdeep.

It's worth pointing out that the duergar alliance could easily be a potential source of faction intrigue, but it’s not. Despite a table showing that some of the elements within it are hostile to each other there’s nothing to indicate how its various parts can be pried apart or what the entire coalition will do when faced with effective opposition. What will it take to turn the trolls against the duergar? We don’t know. The two headed troll chieftain is just a stat-line without desires, goals, fears, schemes or a personality.

|

| The Missing Exile Army? Dwarf Wars - John Blanche Again |

A third faction potentially exists in the form of the overland groups - especially the exile dwarves who wish to return home. Ultimately Dwarrowdeep abandons this plot line though. As noted above the town of Hamelet is exhaustively detailed, down to the predictable customs and trite “dwarfied” slang. Every major NOC in the town, and many minor ones are provided -- but like the rumor table there’s nothing there to motivate play, and no hooks to engage in faction intrigue.

Several times in the adventure notes that the exile dwarves send raiding patrols into Dwarrowdeep but besides a few dead and the occasional captive this doesn’t have an impact or a meaningful model in the adventure. Let the players earn the dwarves trust to lead these patrols, offer a way for the exile dwarves to gain confidence and start launching larger expeditions. A simple faction chart showing resources and a list of misisons/goals would do wonders here. Even the numerous dwarven slaves within the mountain lack the potential to become a meaningful opposition to the duergar. The only groups of powerful dwarven captives (4th - 6th level fighters - still not much against 4th level duergar hordes) are in the last few areas, the fortresses and storengholds - meaning there's no option for them to be freed and return to the mountain for vengence, properly equipped and healed. Dwarrowdeep fail to give sufficient information about the order of battle for any exile dwarven faction or provide them with goals and motivations, but even with these additions and the other's I've suggested, the hit dice and ability differences between the exile dwarves and duergar are simply too great for any exile force to have a meaningful chance of recovering or holding any part of the mountain. It's deeply unfortunate that not even the slightest attention was paid to designing Dwarrowdeep around the possibility that the exile Dwarves or perhaps some force within the dungeon could raise a significant armed group to challenge the duergar in battle.

This is a shame, because without faction intrigue, base building/reclamation, or larger scale battles the fundamentally repetitive nature of Dwarrowdeep’s design is even more clear - it can’t be avoided - every delve into the underhome must be more or less the same assault on a humanoid garrison by the party. Again, one can’t really run a Moria campaign with Dwarrowdeep, because there’s no way to take and hold space within -- Balin’s expedition is impossible. The adventure has to be resolved (even as the party approaches 10th level) through skirmishes between the party and the humanoid groups within Dwarrowdeep.

Some will push back here (and on the idea that the Hammer of the Dwarven Kings should have greater ability to resolve the megadungeon) out of the misguided idea that offering these possibility of a conclusion is inserting story or a railroad into a sand box adventure - it's not, it's providing possibilities for players to create a story - not setting up a series of inevitable scenes. This distinction makes all the difference. Like a regional setting, a megadungeon works best as a place full of coiled potential: tight balances of power and ways for the characters to push static situations into chaos and activity. The idea of faction intrigue as a secondary mode of play in large adventures is as old as the hobby, and that a campaign can culminate in mass combat is even older, despite mass combat having been set aside for much of the TSR era.

In contrast to Dwarrowdeep, Dragon Mountain (which is again not an amazing megadungeon by any standard) the humanoid population is largely made up of varied color coded kobold bands - their territories explicitly marked on the map and their hostilities documented. The party can fight, negotiate, trick, and play the humanoid factions against each other to make their way to their dragon overlord, and this produces a greater variety of play with more options, despite Dragon Mountain’s somewhat more limited selection of monsters and smaller size. With adventures as old as Dragon Mountain, Caverns of Thracia and Vault of the Drow as examples Dwarrowdeeps static, unambitious groups of humanoids both in and outside the dungeon are a travesty.

SECRETS AND MYSTERIES

The reason factions are important is because they allow and encourage player choice and engagement with the adventure or setting. The larger the adventure, the more important it is to encourage player involvement, to provide both immediate and multi-session goals that function as small victories or moments of excitement and wonder. Dwarrowdeep’s conscious decision to use a well known aesthetic and cliched description almost prevents it from creating wonder as the players are very likely to already know exactly what everything looks like within the dungeon, but it leaves plenty of space for engaging players with excitement, and minor victories.

Goals are best when they are self-generated, players will get more enjoyment out of accomplishing some sort of quest or fulfilling some sort of scheme they set for themselves then completing one provided by an NPCs. Of course without information players can't develop their own plans so, hooks and rumors are used provide starting motivation. Dwarrowdeep doesn’t have effective hooks or rumors, just the vague idea that maybe the party could explore its enormous dungeon where there is treasure, and some exiled dwarves would be happy if they reclaimed it somehow. To repeat a theme in this review … it lacks the rumor of Durin’s magic crown drowned in the depths.

However, hooks and rumors aren’t the only way to produce engagement just a first step -- the dungeon itself can give clues and signs of larger mysteries or smaller secrets. At the most simplistic level this comes down to keying - clues to a secret treasure cache and the like (which Dwarrowdeep manages occasionally). Especially in an adventure the size of Dwarrowdeep, larger mysteries or potential events and escalations are beneficial, and Dwarrowdeep even offers one or two possibilities at the grandest scale - while providing almost no means to utilize them in play. For example Dwarrowdeep repeatedly notes that the duergar and exile dwarves are one people, separated by a religious schism, the players can even figure it out, and there's a leader among the exile dwarves who secretly worships the duergar god. Yet nothing is made of this. There’s no corresponding faction among the duergar who want to reconcile with the exile dwarves, or otherwise interact with the overworld. The secret relationship between the exiled dwarves and the duergar is empty “lore”, with no effect on play. Why not offer the possibility to the players that by brokering an alliance (and likely wiping out detractors) they can become the rich benefactors (or founders even if they are dwarves) of a mostly evil dwarf hold? That's a big way to move to domain play.

A slightly more defined set of secrets and a long-term goal is the idea that the party should “Seek the Hammer of the Dwarvish Lords” - a phrase repeated throughout the adventure by various sources, including some of the more friendly ancestral spirits the party will discover.

Several times in the adventure notes that the exile dwarves send raiding patrols into Dwarrowdeep but besides a few dead and the occasional captive this doesn’t have an impact or a meaningful model in the adventure. Let the players earn the dwarves trust to lead these patrols, offer a way for the exile dwarves to gain confidence and start launching larger expeditions. A simple faction chart showing resources and a list of misisons/goals would do wonders here. Even the numerous dwarven slaves within the mountain lack the potential to become a meaningful opposition to the duergar. The only groups of powerful dwarven captives (4th - 6th level fighters - still not much against 4th level duergar hordes) are in the last few areas, the fortresses and storengholds - meaning there's no option for them to be freed and return to the mountain for vengence, properly equipped and healed. Dwarrowdeep fail to give sufficient information about the order of battle for any exile dwarven faction or provide them with goals and motivations, but even with these additions and the other's I've suggested, the hit dice and ability differences between the exile dwarves and duergar are simply too great for any exile force to have a meaningful chance of recovering or holding any part of the mountain. It's deeply unfortunate that not even the slightest attention was paid to designing Dwarrowdeep around the possibility that the exile Dwarves or perhaps some force within the dungeon could raise a significant armed group to challenge the duergar in battle.

This is a shame, because without faction intrigue, base building/reclamation, or larger scale battles the fundamentally repetitive nature of Dwarrowdeep’s design is even more clear - it can’t be avoided - every delve into the underhome must be more or less the same assault on a humanoid garrison by the party. Again, one can’t really run a Moria campaign with Dwarrowdeep, because there’s no way to take and hold space within -- Balin’s expedition is impossible. The adventure has to be resolved (even as the party approaches 10th level) through skirmishes between the party and the humanoid groups within Dwarrowdeep.

Some will push back here (and on the idea that the Hammer of the Dwarven Kings should have greater ability to resolve the megadungeon) out of the misguided idea that offering these possibility of a conclusion is inserting story or a railroad into a sand box adventure - it's not, it's providing possibilities for players to create a story - not setting up a series of inevitable scenes. This distinction makes all the difference. Like a regional setting, a megadungeon works best as a place full of coiled potential: tight balances of power and ways for the characters to push static situations into chaos and activity. The idea of faction intrigue as a secondary mode of play in large adventures is as old as the hobby, and that a campaign can culminate in mass combat is even older, despite mass combat having been set aside for much of the TSR era.

In contrast to Dwarrowdeep, Dragon Mountain (which is again not an amazing megadungeon by any standard) the humanoid population is largely made up of varied color coded kobold bands - their territories explicitly marked on the map and their hostilities documented. The party can fight, negotiate, trick, and play the humanoid factions against each other to make their way to their dragon overlord, and this produces a greater variety of play with more options, despite Dragon Mountain’s somewhat more limited selection of monsters and smaller size. With adventures as old as Dragon Mountain, Caverns of Thracia and Vault of the Drow as examples Dwarrowdeeps static, unambitious groups of humanoids both in and outside the dungeon are a travesty.

SECRETS AND MYSTERIES

The reason factions are important is because they allow and encourage player choice and engagement with the adventure or setting. The larger the adventure, the more important it is to encourage player involvement, to provide both immediate and multi-session goals that function as small victories or moments of excitement and wonder. Dwarrowdeep’s conscious decision to use a well known aesthetic and cliched description almost prevents it from creating wonder as the players are very likely to already know exactly what everything looks like within the dungeon, but it leaves plenty of space for engaging players with excitement, and minor victories.

Goals are best when they are self-generated, players will get more enjoyment out of accomplishing some sort of quest or fulfilling some sort of scheme they set for themselves then completing one provided by an NPCs. Of course without information players can't develop their own plans so, hooks and rumors are used provide starting motivation. Dwarrowdeep doesn’t have effective hooks or rumors, just the vague idea that maybe the party could explore its enormous dungeon where there is treasure, and some exiled dwarves would be happy if they reclaimed it somehow. To repeat a theme in this review … it lacks the rumor of Durin’s magic crown drowned in the depths.

However, hooks and rumors aren’t the only way to produce engagement just a first step -- the dungeon itself can give clues and signs of larger mysteries or smaller secrets. At the most simplistic level this comes down to keying - clues to a secret treasure cache and the like (which Dwarrowdeep manages occasionally). Especially in an adventure the size of Dwarrowdeep, larger mysteries or potential events and escalations are beneficial, and Dwarrowdeep even offers one or two possibilities at the grandest scale - while providing almost no means to utilize them in play. For example Dwarrowdeep repeatedly notes that the duergar and exile dwarves are one people, separated by a religious schism, the players can even figure it out, and there's a leader among the exile dwarves who secretly worships the duergar god. Yet nothing is made of this. There’s no corresponding faction among the duergar who want to reconcile with the exile dwarves, or otherwise interact with the overworld. The secret relationship between the exiled dwarves and the duergar is empty “lore”, with no effect on play. Why not offer the possibility to the players that by brokering an alliance (and likely wiping out detractors) they can become the rich benefactors (or founders even if they are dwarves) of a mostly evil dwarf hold? That's a big way to move to domain play.

A slightly more defined set of secrets and a long-term goal is the idea that the party should “Seek the Hammer of the Dwarvish Lords” - a phrase repeated throughout the adventure by various sources, including some of the more friendly ancestral spirits the party will discover.

It means almost nothing.

The hammer and the Forge of Creation are within Dwarrowdeep, but they are simply a powerful weapon, they may improve the PCs abilities to wreak havoc on the Duergar, but the hammer doesn’t have any other secret to it, it offers no resolution or interesting shift in the relation of the party to the mountain, either group of dwarves or anything else. In Dwarrowdeep a hammer is just a hammer, no matter how much various dwarf ghosts insist otherwise.

Even At the final confrontation with the duergar - their arena and kingly halls, Dwarrowdeep provides no support and almost no possibility for interaction or climax beyond a series of ever more difficult combat encounters. The only results from finally discovering the duergar stronghold that the adventure supports are: its destruction, death of the party, or the party’s enslavement. No secret or mystery will give the party a great advantage or provide alternatives. As mentioned, the discovery of the hidden Dwarven Forge of Creation and Hammer of the Dwarvish Lords -- repeatedly held up as the goal of the campaign and solution to the duergar problem -- doesn’t offer that much. The artifact is a powerful, but not overpowering, weapon and it will not really change the balance of power between a 10th level party and the armies of the dark dwarves: they won’t run from it, offer to trade it for the mountain home, or recognize the wielder as King, they’ll just take more damage from being hit by it.

At least the keying of final duregar redoubt considers the obvious possibility that characters may be captured by the duergar and most likely thrown into the arena as gladiators. Sadly while capture is suggested, the arena is only hinted at by implication and almost nothing is provided to support this possibility or that of escape from duergar captivity.

Like so much of Dwarrowdeep, finding this artifact is a very empty sort of triumph.

It's not just the grand mysteries and campaign goals that are missing. Less important secrets are also omitted, though the basis for a few is provided in the indulgent (because it has almost no impact on play) introductory section. For example, pages are spent on dwarven culture - bland stuff of course, derivative and likely easy enough for anyone who has any association with the fantasy genre to make up. This information though could matter, it could be the source of solutions to puzzles and secrets within Dwarrowdeep, and at least in one case it is, but mostly it's just meaningless fluff.

The existing use of secrets does more to prove this argument then improve the adventure. Dwarrowdeep obviously knows how clues, secrets, and mysteries sort work, because it includes a set of dwarven mine markings that can be decoded or discovered and are occasionally noted in the text, most often warnings against upcoming hazards. It's a secret language the players can learn to help them explore - precisely the sort of little triumph that most players find exhilerating.

There's just that one though, and there are so many more similar possibilities, even in the sort of standard fantasy background Dwarrowdeep revels in. As one example: the introduction also spends ½ a page on dwarven beards and their cultural significance … it’s just not useful information.

It could be.

Dwarrowdeep could have its dwarven ghosts react differently based on character facial hair, making party grooming an important decision, or it might include puzzles with solutions based on recognizing beard styles and their meaning in carvings, tomb effigies and such. "Pop the lid of the tomb with the forked bearded dwarf on it - it's the sign of the gem makers - avoid the one with the four plaits tied in knots, that dwarf was an apostate of the balrog possession cult."

Even At the final confrontation with the duergar - their arena and kingly halls, Dwarrowdeep provides no support and almost no possibility for interaction or climax beyond a series of ever more difficult combat encounters. The only results from finally discovering the duergar stronghold that the adventure supports are: its destruction, death of the party, or the party’s enslavement. No secret or mystery will give the party a great advantage or provide alternatives. As mentioned, the discovery of the hidden Dwarven Forge of Creation and Hammer of the Dwarvish Lords -- repeatedly held up as the goal of the campaign and solution to the duergar problem -- doesn’t offer that much. The artifact is a powerful, but not overpowering, weapon and it will not really change the balance of power between a 10th level party and the armies of the dark dwarves: they won’t run from it, offer to trade it for the mountain home, or recognize the wielder as King, they’ll just take more damage from being hit by it.

At least the keying of final duregar redoubt considers the obvious possibility that characters may be captured by the duergar and most likely thrown into the arena as gladiators. Sadly while capture is suggested, the arena is only hinted at by implication and almost nothing is provided to support this possibility or that of escape from duergar captivity.

Like so much of Dwarrowdeep, finding this artifact is a very empty sort of triumph.

It's not just the grand mysteries and campaign goals that are missing. Less important secrets are also omitted, though the basis for a few is provided in the indulgent (because it has almost no impact on play) introductory section. For example, pages are spent on dwarven culture - bland stuff of course, derivative and likely easy enough for anyone who has any association with the fantasy genre to make up. This information though could matter, it could be the source of solutions to puzzles and secrets within Dwarrowdeep, and at least in one case it is, but mostly it's just meaningless fluff.

The existing use of secrets does more to prove this argument then improve the adventure. Dwarrowdeep obviously knows how clues, secrets, and mysteries sort work, because it includes a set of dwarven mine markings that can be decoded or discovered and are occasionally noted in the text, most often warnings against upcoming hazards. It's a secret language the players can learn to help them explore - precisely the sort of little triumph that most players find exhilerating.

There's just that one though, and there are so many more similar possibilities, even in the sort of standard fantasy background Dwarrowdeep revels in. As one example: the introduction also spends ½ a page on dwarven beards and their cultural significance … it’s just not useful information.

It could be.

Dwarrowdeep could have its dwarven ghosts react differently based on character facial hair, making party grooming an important decision, or it might include puzzles with solutions based on recognizing beard styles and their meaning in carvings, tomb effigies and such. "Pop the lid of the tomb with the forked bearded dwarf on it - it's the sign of the gem makers - avoid the one with the four plaits tied in knots, that dwarf was an apostate of the balrog possession cult."

These seemingly conscious design decisions: to pad the keys and setting of Dwarrowdeep without connecting its elements or incorporating its mysteries in an actionable way are inexplicable. The tools exist within the adventure, but Dwarrowdeep only provides secrets in the most basic forms: a key to a secret door ten rooms away or a vague suggestion that there might be treasure somewhere far away. These kinds of secrets aren’t really something to seek out, and information about the mountain's past, or its mysteries isn’t ever especially valuable or accessible to the players. Ultimately Dwarrowdeep is simply rooms filled with foes, the occasional ally or treasure, and traps. There is little connection for players to discover between its numerous humanoid lairs, and no point in doing so anyways because no advantage is gained, no mystery solved, curiosity and discovery just provide a few random bits of useless information that don’t change the course of the adventure. One might say Dwarrowdeep passively punishes intelligent play and engagement by making it a waste of time.

KEYS, INTERACTIVITY AND VARIETY

The individual keyed locations to Dwarrowdeep are likely its strongest traditional element, but they are still marked by 1980’s TSR design conventions, especially those of the early BECMI era, and they include some of its pecularities that work against utility. The keys of Dwarrowdeep, like those of the adventures it models, often stumble when it comes to interactivity even within the context of minimalist key design, and finally, at least partially because of the adventure’s scope and limited number of environments and challenges, the keys quickly become very repetitive - the same ideas are recycled almost every level or node of the dungeon.

Keying and interactivity is still an area of discussion in adventure design, but in the past fifteen years or so a list of (admittedly contested) maxims have solidified around what makes a good or bad key. At the simplest and hopefully non-controversial level a good key is one that is both easy to use in play and inspiring. Perhaps this can be described as the tension between brevity and evocative detail -- A dungeon should be the opposite of this review.

The basic structure of dungeon crawl style play (at least when it’s not aiming to be boardgame like) is: referee description of the environment, player questions about aspects of that description, referee response, and player decisions about how to act.

Dungeon keys are useful to this structure as they provide a basis for an environment's description by the referee and ideally details to answer the players’ most likely follow up questions. It’s best to do this efficiently, and largely Dwarrowdeep is often efficient at providing basic descriptions, but it starts to struggle in offering details that the players can interact with after that basic description.

There’s also typical minor issues with the keying that were especially prevalent in TSR products of the 1980’s.

For example there’re keys that include inaccessible information or history:

“Beholding this chamber during the Golden Age of Gundgathol would have been a majestic sight: dwarven guards at their posts, the hustle and bustle of mountainfolk going about their daily routine, and caravans slowly making their way to trade with Hamelet.”

“The stone door to this chamber lies in pieces on the ground. Centuries ago the duergar broke into this chamber with the hope of penetrating the inner crypt. Two sentinels destroyed many of their warriors before they were defeated. The cost was so great they cursed the place in Dworgrim’s name and refused to return.”

Similarly there are a few keys that ascribe emotions to the characters who enter the space:

“The Hall of Stone is sublime. The long vertical lines of the pillars stretch upward and disappear into the darkness while reducing the agency of those who behold it. To some the feeling of being dwarfed by the sheer enormity of the hall is akin to a spiritual experience - specifically feeling the presence of Thaneduhr or Dhurindain in Gundgathol.”

The use of inaccessible historical information and even keys that impose an emotional response on the characters (unless it’s a magic effect - and it’s somewhat unclear above) are minor sorts of errors, but ones very typical of BECMI era dungeon design, as is the major issue with Dwarrowdeep’s keying -- it’s designed almost entirely for combat encounters.

Most of the keys in the adventure are very short, almost in the laconic style of Gygax, except where they include either monster stats (or long lists of gemstone treasures) and, to Gillespie’s credit, monster tactics. Tactics and stats are are good, and it’s one of the few consistent elements in the adventure’s keying that’s a solid positive. Monster tactics promote more interactive, more complex, and more interesting combat because they offer the referee ideas on when and how various creatures fight.

Unfortunately the same rigor hasn’t been applied to non-combat obstacles, or even monster goals and personalities, meaning that just as with its aesthetics and the overall structure of its regions, Dwarrowdeep creates monotony. The specific issue that most of the encounters in Dwarrowdeep are almost inevitably combat encounters (or at least they appear designed with that expectation) is tied to its problems with faction intrigue, but its lack of variety and interactivity in non-combat experiences is a separate and unique issue.

Dwarrowdeep also has traps in it - admittedly not a surprise. These aren’t the complex puzzle traps of Tomb of Horrors, but either simple mechanical or unexplained magical traps. I call these sort of traps “hallway traps” from the ones used by OD&D's Underworld & Wilderness Adventures. They are effectively incidental taxes on character HP for moving through the dungeon or interacting with treasure, as almost universally they do damage when a PC passes a certain point, opens a door, or messes with chest. The party will encounter a lot of chests with poison needle traps, and a fair number of carved mouths (bearded of course - but not with a beard that notably denotes danger - see it could be so easy!) that breathe things or cast spells. Notably even these simple traps, and the secret doors of Dwarrowdeep, are not interactive in the sense of offering puzzles for player ingenuity to solve -- they don’t give meaningful clues about how to disarm or discover them beyond the rules based solutions of thieves’ skills or search rolls. This is unfortunate, because once again traps are interactive traps and puzzles are a way for Dwarrowdeep to offer more than combat with increasingly powerful funny looking not-people in stone corridors. Even hallway traps, are an opportunity to provide some small measure of interactivity for players, but to do so they have to offer clues that they exist and sufficent description for specific player solutions (cut the tripwire with a spear, jam the acid sprayer with a rock etc). Again Dwarrowdeep choses not to bother, to just throw things back to the mechanics of BECMI and players exploring it will still have little to look forward to besides endlessly "rolling for initiative".

Moreover, the few more puzzle-like obstacles that a party going through more than one of Dwarrowdeep's regions will discover are repeated often: all important tombs are false tombs with a nearby haunted true tomb and almost every corpse has rot grubs in it waiting to punish the curious. At least the monsters’ captives aren’t all ready to betray the party in a parody of B2 Keep on the Borderlands (though more should betray the party given the number of captives the party can encounter, because after 250 years some of those captive dwarves have gone over to the duergar). This is emblematic of one of the major issues in Dwarrowdeep is meant to be played beyond a few sessions. Dwarrowdeep doesn’t improve or change, it doesn’t get more complicated or add new challenges. The only real difference between its entrances and its urban core are that the foes in later humanoid forts have higher HD, more magic, and are sometimes better organized. Despite these siege regions offering the only potential variation in challenge design, Dwarrowdeep still won't offer an order of battle and means that if the duergar, derro or fishmen (whatever they are called) sound the alarm it will be considerable referee effort to count up the surviving foes and decide how they act without assistance from the dungeon.

PROCEDURAL GENERATION

I’ve saved the most unfortunate, but most understandable, failure of Dwarrowdeep for last. While there is no excuse for a lack of factions, bloated and repetitive keying, or a lack of secrets and mysteries that create connectivity and player engagement -- certainly no excuse in 2022 -- difficulties in any attempt to use procedural generation for an enormous dungeon are understandable. Procedurally generating dungeons is a hard trick to pull off, and one that designers have been trying with very limited success since the 1970’s.

Gygax’s first large article on D&D in Strategic Review is a set of tables for producing dungeons aimed at solo play. It’s largely repeated (and expanded on) in the tables at the back of the 1st edition Dungeon Master’s Guide. I think these tables are some of Gygax’s best pure game design work, and they remains relevant and interesting as a model. Like most of Gygax’s design they have a level of unnecessary complexity, but they largely succeed and their excesses are entirely forgivable as they represents a bold experiment in a new sort of art form. Procedural generation has also been a major trend in more recent designs. Most notably the work of Emmy Allen, such as Garden’s of Ynn, which generate highly specific locations. There have been many other interesting experiments in procedural generation in the past few years, including the cavern and underground generation tools in Patrick Stuart’s Veins of the Earth, which are very applicable to Dwarrowdeep. Dwarrowdeep though opts for techniques that are far closer to the earliest attempts at procedural generation.

Randomization is an essential part of location based RPG design - the dice can fill in spaces when players inevitably ask questions or make decisions that the referee or designer haven’t written down or even thought of. Additionally the ”oracular power of dice” and faith in random tables is one of the cornerstones of the OSR play style -- the idea that randomly generated content will be more interesting and unexpected, or at least serve as inspiration through surprising juxtapositions. However, there are risks associated with procedural and random generation, from treasure tables to producing entire dungeons: waste and repetition, and both are something found in Dwarrowdeep.

If the basic idea behind procedural generation is to prepare a set of tables that alone or together fill in unknown or lightly sketched areas of the adventure and so save the designer physical and mental space, these two risks should be obvious. The random generation may not actually save space, or it may not adequately fill in unknowns. Waste is easier to point to and endemic in adventure design, especially when the designer doesn’t really grasp the play or design style of older games. Repetition is less of a risk and tends to afflict larger products such as megadungeons or the implied setting produced by rulebooks.

Designers often use random tables in an adventure when they don’t need to: the random table fills more space then the content it would generate, with no advantage. This kind of table abuse wastes valuable pages, forces the referee to stop and roll, and offers less opportunity to provide information or theming for the adventure. For example, in one well-known recent adventure there’s a six entry table for a single treasure that the party has a chance to discover if they dig up the floor of a cellar. Why? It’s not as if the players will be digging up multiple cellars or there are multiple treasures to find. It’s a waste of everyone’s time, and this treasure could be a much stronger part of play if it was a specific thing that related to something else nearby or provided some kind of clue to some other aspect of the adventure.