Hey! Welcome. This is my first review on

Bones. I’m calling them my eldritch

mousetraps, since my online moniker in all the places you can find me is @eldritchmouse. Thanks to Anne for the

great name suggestion!

I’ll be reviewing Death in Space, so strap in,

suit up, and get ready to blast off.

Introduction

Death in Space is a science-fiction RPG with

old-school sensibilities. It was created by Christian Plogfors and Carl

Niblaeus and published by Free League Publishing.

I haven’t had the chance to actually run the

game: this review is based on the PDF copy I received for backing the

Kickstarter.

The real question here is simple—does it hold

up to Mothership, the current big dog in the sci-fi RPG atmosphere?

The Review

We start off strong, with reference tables.

The beginning of the book starts with equipment lists on the inside cover. I’ve

always considered equipment lists to be neat little wishlists that the players

love to look at and use to solve problems. Putting it in an easy to find place

means there’s no digging through the book for it later. How does the equipment

in DIS hold up? Well, you’ve got the good stuff like a fake grenade, pheromone

spray, an animal replica with a simple AI, and magnetic boots.

You’ve also got a table of foodstuffs that is

filled with things like “almost bread,” “toothpaste-type tubes with pureed food

ready-to-eat,” and “vacuu-ice, cold flavored ice in plastic bags.” The fresh

fruit and vegetables are the most expensive things on the list, apart from a

box of spices. They’ve made a deliberate choice

here, to use half a page just for food items, and I think it pays off—the

choices presented imply a strong setting. You’re out in space, and every gram

of weight is worth something. There’s no fancy luxuries.

We dive into the world of the game with eleven

paragraphs of history, laying out the lore we’ll leverage in our campaigns.

Tropes can be helpful in RPGs—a nice anchor to understand the world that is

easy to grasp. DIS employs the standard tropes liberally. There’s a void out

there in deep space, and it uses radio static to call out to you. After an

all-out-war, resources have dried up, so there’s no new spaceships being built.

The central powers are destroyed, leaving behind scattered warlords and their

domains.

Players are hard-working laborers who take

whatever jobs they can get—salvagers, escorts, prospectors, and everything that

slots in between that space.

Even if we don’t leave the RPG medium, we’re

seeing these tropes being used in other places already: in Traveller, in

Coriolis, and in Starforged. The world is gritty, it’s falling apart, and

you’re just in it to survive, job to job. It’s a good and usable setup for a

game, but it’s definitely familiar.

The Iron Ring provides a sort of “starting

village” mixed with a megadungeon to get your campaign rolling. It’s a bunch of

old ships and stations stitched together in a ring around a moon. This is a

very cool concept, as long as you don’t think too hard about just how many kilometers of derelicts you’d need to ring a moon.

Character Creation

|

| The art in the book is wonderful. Evocative, gritty, and full of flavor. |

The system itself for play is pretty

bare-bones. We’ve got 4 abilities, and they’re generated using 1d4-1d4, which

means that you’re most likely to have a 0 for a starting attribute, and a ~6%

chance of having either -3 or 3.

Picking an origin is next: they’re interesting

choices without being too far fetched for our grounded, sci-fi world. The

closest thing to a “baseline” human is a punk, while you’ve got other things

like void shamans, cyborgs, and space vampires (sorta, they have a pod that

regenerates limbs and stops them from ageing.)

The rest of your character is background,

trait, drive, looks, and past allegiance. There’s no mechanical weight to any

of these things, they’re all flavor. Each one has 20 options to roll or choose

from, except allegiance, which narrows down to just 6.

The most flavor is nested in the background

table: the technomant, event horizon diver, static noise translator, and

gravity swindler. These are some neat combinations that gets my brain firing.

Unfortunately, apart from the background

table, the rest of the tables lack flavor. Traits are things I’d expect (proud,

lazy, creepy) and drive is almost completely setting neutral. Past allegiance

is particularly disappointing to me, since it’s mostly things like “family”

(space Dom Toretto), the “winning/losing side”, and “an idea.” We’ve been

presented with a setting full of failed megacorps, space warlords, scavengers,

void callers, and the entirety of the Iron Ring. I think the past allegiances

table could have been jam-packed with setting specific entries that help

players ground themselves and tuck into the world. The options presented are

serviceable, I just wish they had taken it one more step: have the 6 general

choices, with 6 specific ones nested underneath. That way, if the player

somehow rolls the same as the person beside them, they’ve immediately gained a

fun connection.

Last step: starting kit, a starting bonus, and

a personal trinket. The bonus is neat, with things like an AI guard animal,

another person who just likes to hang out with you, +3 hp, or even a cosmic

mutation. The personal trinket table is filled with flavor. “Cartridge with AI

from a dead pet” hits hard. “Notebook with names of people that have treated

you badly” doesn’t really help the setting, but it’s neat to base a character

off of that. “Belt buckle with hidden star compass” is just neat.

Hub Creation

“The hub is

your home, your sanctuary in a tough universe. The crew starts with a station

or a spacecraft.”

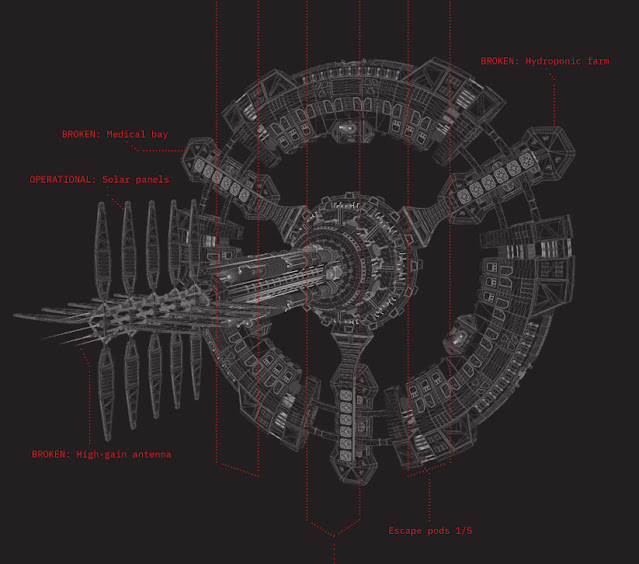

|

| Wireframe schematics and clean lines? Yes please. |

The nature of RPGs set in space means that

you’re usually flying around in some kind of vessel. In DIS they’re letting you

make that choice right off the bat: do you want a ship or a station? Are you

going to travel or try out a more stationary campaign?

The hub rules are simple, but they’re not the

same as characters. You’ve got a power source and modules, and you need to feed

it fuel to power it. It takes 1 fuel per session. This is a bit of a strange

choice with the nebulous amount of in-world time a session can encompass, but

for simplicity’s sake you can’t beat a non-diegetic requirement. Getting more

modules requires adventuring, along with upgrading your power source to power

them. You start with no modules.

There’s two 20 entry tables for hub

backgrounds. The backgrounds are dang good: “Was part of the renowned Eyemaster

squadron of the Union Alliance fleet” and “Used to be a well-known memory

brothel, where one used chromes to share memories and indulge in pleasure

hacking.” The station backgrounds also hit: “Used as an illegal designer drug

lab. Drugs were made from strange fruits harvested close by.” and “Some parts

of the hub have turned into organic material after a mold infestation.”

Each hub gets a quirk too. These aren’t

setting specific, but that’s okay: they’re loaded with flavor and things that

your PCs will (love to) hate.

Playing the Game

The four abilities are Body, Dexterity, Savvy,

and Tech. Interestingly, Tech governs ranged attacks, not dexterity. Checks are

made with 1d20 + Stat (somewhere between -3 and 3, remember) against a static

DC of 12. A failure is serious: you suffer a complication or setback and also

gain one void point.

Inventory is slot based, and there’s included

reaction roll tables.

You can have up to 4 void points at once. You

can spend them to gain advantage on a check or activate cosmic mutations. If

you use a void point for advantage, and also

fail, you’re now rolling to check against void corruption. This is another 1d6

roll, and if you roll below or equal to your current void points, you suffer

corruption.

Honestly, that’s a lot there for a single

roll. Let’s think about it in an example. I have 4 void points (max), and the

GM calls for a roll. I spend 1 void point to get advantage but fail the check.

Now I roll against cosmic mutation, rolling a 1d6 and trying to beat a 3. If I

fail that, I’m rolling a 1d20 on the void corruptions table.

Void corruption is interesting design. If

you’re scared of corruption, you want to burn your void points right when you

get them: if you only have 1, you can’t get corruption when you spend it. If

you’re maxed out, there’s a 50% chance you’re getting corruption. The

corruptions themselves are a big mixture of things, including body mutation,

mechanical stuff, and a few ambiguous things left to the referee.

The cosmic mutations are very magic-feely.

There are things here like mutations that let you eat anything and heal from it, things that let you teleport to places

you’ve seen in the past, ways to warg into smaller creatures, and the ability

to control tech. Since void points power these, you’re only using them when

you’ve failed previous rolls. Using a mutation doesn’t trigger a corruption

roll though, so it’s another safe way to burn through points.

I don’t like when games gate things the

players want behind failed rolls. Another example could be some PBtA games,

where you mark XP for failing a roll, or get XP just for rolling your highlighted stats. Once you figure that out as a player, you

can begin gaming the system. In DIS, you’re using void points for your powers,

so you’ll need to fail rolls to activate them. Which means that it’s likely

you’re going to push for more rolls—especially things you might fail in—to

accumulate points. Now this puts the referee in a difficult position, because

having characters roll for everything doesn’t

make sense, so you have to decide… well, what makes something worth a roll?

This is a strong design issue that irks me.

When every single roll has the potential to be generating something, you’re now dealing with the ambiguity of how often and

when you should roll. In the perfect vacuum of game design, the answer is easy:

Only roll when the stakes are high! Only roll when failure is interesting! Only

roll if the characters have a chance at success! To some degree, whether it’s

story games or OSR, there’s talk about “when to roll.” And therein lies the

problem.

In the real world, when I’m hanging out with

my friends, it’s fun to just roll the dice sometimes.

I love a good moment at the table when

everyone is laughing and having fun, and someone proposes a situation that’s

ridiculous. “Oh, you want to try and impress this spacer by doing a standing

backflip in full gravity? Okay… well, that’s not going to be easy. Roll

Dexterity. If you get a 20, we’ll say it happens.” Everyone laughs, the dice

hit the table, and no matter the result, we’re having fun. In design like this,

you either don’t worry about that too much (oops you failed your backflip but

got a void point) or you say “nope, you don’t know how to backflip, it doesn’t

work.”

This is why I find the “every roll creates

something” design to be such touch and go. I don’t think that this ruins the system at all, and for most

tables out there, I wonder if this even comes up? All I can speak for is my own

experience, though. There're certainly other ways you could use to generate

void points that doesn’t put such an onus on the referee and calling for rolls.

The easiest one that pops to mind is that you generate a void point when you

take damage. Using them follows the same rules.

|

| This person definitely says "hello" to the void as often as possible. |

Moving on! All gear in the game has Condition.

This hammers home that duct tape and superglue are holding the world together.

Everything kinda sucks, and it’s always needing repairs. Each time you use the

gear in a stressful situation, check against condition. Very simple and easy.

Repairing stuff happens with spare parts;

recover them by dismantling anything you can get your hands on: electronics,

equipment, vehicles. It all boils down to spare parts. For smaller stuff, it’s

1d6 hours. For bigger stuff, it’s 1d20 hours.

EVA suits for difficult environments are

detailed, and the important thing about them seems to be their oxygen capability.

The character sheet even has an oxygen meter, and all suits have enough O2 for

7 hours.

Time, however, is very loosely defined in the

book. Apart from the aforementioned repairs, oxygen, and some upcoming travel

times, it’s not a big deal, mechanically. As mentioned earlier, power cells

deplete once per game session, instead

of any sort of game clock. If repairing stuff takes 1d6 hours, what does it

matter if it’s 1 hour or 4 hours? If you’re in a crunch, sure, but when you are in a crunch, there’s no time-keeping

rules for what you can do during that

crunch. Suits have 7 hours of oxygen, but that’s only coming into play when the

referee says, “okay, it’s been another hour. Lose O2.” There’s no other details

about what you can get done in an

hour.

In these newer OSR games, time is often

omitted, apart from strange artifacts left in the usual places. I wish the game

had a more stricter or defined “turn system” regarding time-keeping.

Space Travel

There’s not much here, mostly just dealing

with fuel usage and encounter tables. There’s no determined travel times, just

a graph based on your speed. There’s non-cryo sleep travel, cryo-sleep travel,

and “bridging” travel, which is near-instantaneous but very expensive.

Anything that isn’t within system is going to take a long time unless you bridge. I’m

talking years and decades. In this game, you’re either staying in the same

system or using the bridges to get across: otherwise, the referee is dealing

with huge gaps of time to fill in between travel. Those situations can be a lot

of fun at the table, and I would have loved a “here’s what’s changed” random

table to help grease those wheels.

Combat

Initiative is elective action order: you

choose who goes next, until everyone’s gone, and then it’s a new round.

Otherwise, it’s the pretty standard OSR combat you’re expecting.

Space Combat

There’s a broad list of actions and a narrower

list of module-specific actions, but there’s no actual rules for what the

actions do—it’s up to the referee to figure that out.

Spacecraft have “frame damage” which functions

as HP. It’s from 1-100, as a percentage, but only uses 10% increments. So it

could have been from 0-10 without any changes. It feels like they’re trying to

emulate that “hull damage at 30%!” stuff, but I’m not sure I see the point.

After the fight, fixing superficial frame

damage is quick and easy. At 50% frame damage, you suffer a disaster, and these

are pretty devastating. As such, space fights are not encouraged: board instead

of bomb.

|

| The space combat uses range bands and abstract positioning. |

Advancement

There’s no traditional levels or classes.

Instead, you gain XP by answering questions at the end of the session, such as:

did you deliver on a dangerous contract?

Did you use at least 1 void point? Did you gain a new enemy?

When you’ve got enough XP you can spend it on

individual increases to various things.

Extras

Random tables, setting info, and extra bits

fill out the back half of the book.

Locations

Since this system makes it costly in resources

and time to travel to different systems, there’s a hefty chunk of the book

spent on the Tenebris system. You could set an entire campaign here, and I

think that’s the default assumption. With sci-fi games like this, I think

there’s a tendency to spread lore wide rather than deep, so focusing on

Tenebris is a good decision. I’m positive that there will be more books with different

systems down the road, depending on the game’s success.

Tenebris itself has 14 locations detailed out,

getting somewhere between ~30 to ~140 words. It’s not much in terms of size,

but the locations are primed for adventure. This isn’t a lore-heavy gazette of

places in space.

For a few examples:

There’s Amissa,

which has The Block. It’s a maze like city of poverty and power, and you could

set standard cyberpunkish adventures here, right out of the box.

There’s Lepidoptera,

a planet covered in jungles and old ruins. It’s under barrage by solar

storms too, which mess up your electronics—the perfect place to set some more

standard style dungeon crawls.

Ogre

houses The Abyss, an active research station delving into the

secrets of the universe. It works well as a “mission-giver” or a place of

interest, especially after something goes horribly wrong with the research

base…

I’m confident that all 14 locations have, at

the very least, the seed of adventure in them. While they might not have

outright hooks listed, it’s not a tough stretch of creative muscles to create

something interesting.

Cults

Next up: four cults, one column for each

spread across two pages. These are self-contained factions, and there’s lots of

detail contained in the condensed space. Each has a nice writeup, and then

they’re populated with keywords for: Looks, Belief, Goals, Leader, Scarcities,

Abundancies, and Theme. The cults themselves are made up of isolated psions,

con artists, void chasers, and monstrous mutations.

One thing that’s a bit weak in this area is

the connections between each cult. They do cross a bit between scarcities and

abundances, but none of them are in direct conflict with any of the others.

With only four factions, pushing them into immediate conflict with each other

would have upped the potential energy of these factions.

When it comes to factions in a game, every

action taken by one group should upset another. Since these cults are the “big

four” in the setting, they should be rubbing against each other for space to

maneuver. Another option (albeit weaker) would be to add another keyword to the

write-ups: Known Enemies. Even if we’re only getting the name of an undetailed

faction, that’s still enough to springboard.

The keywords are a great way to build out

factions, so I would have enjoyed it if they had included random tables to

generate more factions.

Tables and Tools

After the adventure included in the book

(discussed after this section) we get to the last part of the book. We start

off with a table of monsters, 8 in all.

Unfortunately, a few of the included monsters

are a bit bland—the apsis ape is just an

ape and the hairpin pig-folk get 2 lines of text and nothing makes them

stand out (apart from the name, of course).

There are some fascinating ones though: the

Aurora Massworm can atomize organic matter, which is a fun and deadly thing to

even think about, let alone encounter. There’s even a little adventure hook at

the end of the entry: “With the right

tools, the particles can be collected and reassembled.”

The Antfolk bite people and turn the afflicted

body part into nutritious liquid. Yum.

The Neon Harpy rips out memories and turns

them into holographic projections. That’s well primed for an adventure for the

PCs.

If you’re condensing your monster entries to

such a small number, you absolutely need homeruns. I wanted to see more of a

lean towards how these monsters might spur adventures on their own. There’s

some that are easy to use, like the Massworm, but then there’s also others that

are just a deadly swarm of flies that can only take damage from fire. I don’t

think it’s reasonable to ask for an entire monster manual in the book,

especially when there’s so many books

you can draw inspiration from. What I’m looking for here are things that are

creative, original, and exciting. Things that I couldn’t come up with on the

fly during a game, and things that get me thinking about the game during the

off-hours. Use monsters to spark my brain, not to hand me off some stats.

Along with the monsters, there’s also 6

“corruptions of the void” which are more stat blocks. Some of these are

space-zombies with a little twist, but you’ve also got some gross insect-like

things. Not that memorable, unfortunately.

We also get three “beings” connected to the

void. These could be cults, deities, or something more—there’s not much written

on them, just a sentence each.

There’s a neat trap generator, where you roll

a trigger and an obstacle. You’ve got some standard triggers like pressure plates,

but also fun stuff like magnetic detectors and lasers. Obstacles also have a

nice range, like a pipe bomb all the way to a matter-converter where you could

end up with an arm made from bendable glass.

The next tables are random space encounters,

iron ring locations, addictive substances, more equipment, and contractor

(hirelings) stats and rules.

A random contract generator helps you create

random adventures. I generated a few options and got some good ones

● Scavenge a

weapon from a cult at a forgotten mining station. You’ll get paid in new gear.

● Tow a

creature from a planet ruin to a rebuilt satellite for a union worker.

There’s also an NPC generator that cooks up

some neat people:

● Fushigi

Guide: a drone friller. Old-fashioned. Never smiles. Likes things simple.

Untied big boots, patched broken nose.

● Nauka

Atticus: a data-pusher. Speaks with a unique accent. Disarming gaze. No shoes,

tight t-shirt, black pants.

The vibe of the NPCs is good and evocative,

but I would have enjoyed some setting specific tables that hones in on the

needs, wants, and motives of the people here. That would add another vector to

generate adventures, tied into an NPC.

The Adventure: Welcome to the Ring

One thing I’ve noticed with the product lines

that Free League publishes is a dedication to “adventure landscapes” instead of

more traditional linear storylines. In things like Symbaroum, Mutant, and

Forbidden Lands you’re given a sandbox of toys and are encouraged to let your

players run wild. While Death in Space wasn’t written by Free League, it is

published by them, so I’m hoping that it follows the same line of thinking for

adventure writing.

The adventure in the book is a fresh start to

the game—the players start with a broken hub that needs fixing and hit with a

docking fee that they need to pay off to leave. At the same time two gangs are

about to erupt in an all out war in this part of the Ring. One gang controls

the power, one gang controls the computers. They both need each other, and they

both want to oust the other.

There’s also an immediate timer built in: the

higher ups who control this part of the ring are on the way, and when they show

up in four hours, it’s shooting first and questions never. Players need

repairs, fuel, and to pay the docking fee before that happens.

The adventure is split into four and a half

zones, with each one detailed out across two pages. The zones contain

locations, events, people, and factions. Two area maps flesh out the main gang

hideouts.

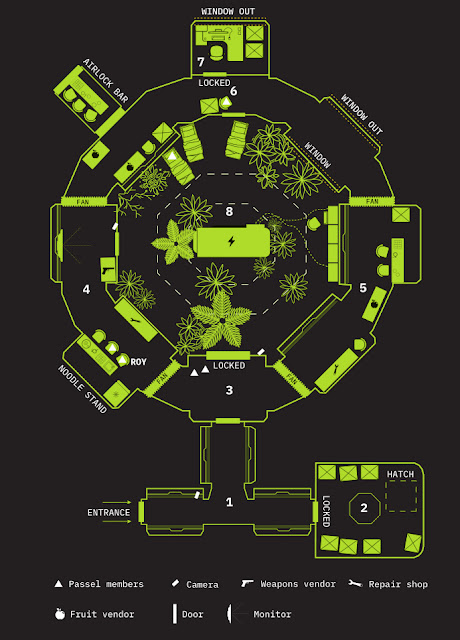

|

| One of the area maps. I love the single color simplicity. |

This is an adventure without a bad guy. Both

gangs are neither good nor right, they’re just people. The setting is bleeding

through pretty hard here—this is a run down place, patched together and holding

on. Virtual reality drugs are rampant and a growing problem, and water is in

short supply to grow the food.

There’s no easy solution. At best, it provides

some “if the players do this…” sections. These two things together are a useful

and desirable way to present the adventure.

The four hour time limit is interesting, but

there’s no procedural way to decide what you can accomplish in four hours of

time. It does imbue a sense of

urgency, and the players might split up—in my mind, the best case scenario

would be the crew splitting up and siding with both gangs, discovering that

there’s no clear winner or bad guy. But the urgency is coming from the

narrative, not from an actual mechanic.

The real problem here is that time passing

comes down to referee fiat. You’re likely to encounter a “just in time”

cinematic solution, which might be

fine and desired for your group. But since this is a rules-light OSR-ish

system, I was expecting a firmer grasp on how time passes. There are no “turns”

that advance time, nor does it say how long it even takes to move between each

node.

Stricter turns could be employed—it takes x minutes to move between the zones, and

you can do one significant action in each node that takes x minutes. However, I don’t think that’s the only option if you’re writing an adventure of this style. I also

think a countdown clock could suffice, where instead of just saying “2 hours

have passed, what now?” the referee has a timeline of events that will occur,

increasing the chaos of the Ring with specific events. Each major action

advances the clock, which the players can always see. You could

improv all this with the information in the adventure, but for me a published

adventure should be providing me with things I can’t think up at the table on

the fly.

When you put an adventure into a rulebook, it

sets the tone, pace, and standards for further adventures. In that way, I’m a

bit surprised this isn’t a space dungeon crawl, but rather a social heavy

adventure with lots of factions and opportunities for roleplay. I think you get

a lot out of 14 pages, including some interesting hooks for further play. This

is an adventure my group would absolutely love.

Conclusion

There was a lot of talk about Death in Space

being very similar in tone and theme to Mothership when the Kickstarter

launched. They occupy similar spaces (hah), but with pretty different rulesets

and design ethos.

There’s no stress mechanics in Death in Space,

but combat is a lot simpler and quicker to run. Death in Space feels much less

like a horror anchored game, and much more in the vein of “hard-working space

truckers.”

Taking the myriad of excellent Mothership

modules and using Death in Space to run them is still very possible, and

conversion would be a snap.

I would have liked more rules, especially ones

related to time, in the book. There’s a lot of rules-light OSR-ish games out

there, and there’s only going to be more. This takes us to the stars, in a

grungy falling-apart future, but is that enough to be novel?

I’m interested to see what kind of support the

game receives after release. The longevity and success is going to depend on

the release of new adventures, and not just standard, predictable ones. The

Mothership community is pumping out some of the most creative modules out

there, and the support they receive from TKG really shows. Death in Space needs

to foster that same support and community.

If you’re looking for rules-light in the

stars, Death in Space is a solid foundation for such a game. I’m hoping we see

some neat and evocative adventure landscapes down the line. On the website,

they’ve just released a third-party license, so I'm

wondering what we'll see from that. If you backed the Kickstarter, there’s also two pamphlet adventures waiting for you. I

haven’t read them, but I’d be eager to see the direction they go in.

I had thought that when I finished writing

this, Death in Space would be fully available to the public, or at least a PDF

copy of it would be for sale. But it seems to be not the case, so instead of a

review, this is a hands-on preview. When it is available, I expect you’ll be

able to get it from https://deathinspace.com/ or

directly from Free League Publishing.

I feel like Death in Space is entering an already-crowded conceptual region - not just with Mothership and the Alien RPG, but Eclipse Phase and Shadows over Sol and assorted other games. And to stick out from the crowd you either need a whole lot of flavor and some noteworthy Big Ideas, or really stand-out adventures.

ReplyDeleteYup! Not to mention Coriolis, Starforged, new Traveller, Vast Grimm, Through the Void, and many others. I think Death in Space has some bits of good flavor, and now needs the support of a few outstanding adventures that leverage it.

DeleteThis sounds really interesting. I can understand your concern about the void points and the nature of rolls, but if I'm understanding correctly, I like the way it encourages players to be constantly using them rather than hoarding them, and it also feels thematically resonant in addition to being a way to get players to use their resources.

ReplyDeleteI do really like that it encourages *using* void points in a few different ways (including granting XP at the end of the session.) It's also good design that you essentially have the choice of either using them right away or hoarding them, based on if you want your character to get a cosmic mutation. (Use them right when you get them: no chance of mutations. Hoard them and it can bump up to a 50% chance.)

Delete