Last year, a white police officer murdered George Floyd on camera, which set in motion uprisings by the Black Lives Matter movement across the United States and around the world. Despite the

remarkably nonviolent nature of these demonstrations,

over 10,000 protestors were arrested by the very police whose

egregious abuse of power they were protesting. Many organizations and communities organized in support of the protests. One such effort, led by the

Whisper Collective, produced Dissident Whispers. All proceeds from the project go towards bail funds, supporting all those arrested for standing up for Black Lives Matter.

Dissident Whispers is an anthology of 58 TTRPG adventures, produced by Tuesday Knight Games in collaboration with the Whisper Collective, made possible through the collaboration of over 90 artists, writers, editors and designers. This issue of Cryptic Signals will not review every adventure in Dissident Whispers, but focuses on a few that catch our individual sets of eyes.

...

Canal of Horrors (Review by WFS)Canal of Horrors is an adventure for Electric Bastionland by Chris McDowall. Like most adventures in the Dissident Whispers anthology, Canal of Horrors is short and sweet, fitting on a two-page spread. It consists of a map of several boroughs of Bastion (“The only city that matters”), annotated with details about each borough and a simple adventure hook and things that get in the way. In short, it has everything needed to inspire an adventure.

McDowall is often praised for his terse style, both in his advice and his rules. He has a much-lauded ability to cut rules to the core. As Anne of DIY & Dragons said,

“I consider Into the Odd to be something like the Platonic ideal of simple Dungeons & Dragons. Both the rules and the writing have been distilled down to their very essence and presented in the tersest, most compact possible way, without sacrificing the elements that are most essential to play. I'm not saying that no one else can write something better than I2TO, but I am saying that you'd be hard pressed to write something shorter. Chris McDowell has seemingly cut out everything but the most necessary elements of D&D, and edited his own writing to be as terse as possible.”

What goes less-often commented on is that McDowall is one of the funniest writers in TTRPGs. While his description of the “Rich Future Bastard Versions of You” pursuing the player-characters cracked me up the most, almost every entry in Canal of Horrors matches the understated comedic tone. It isn’t trying to be funny; it just is. The worldbuilding hits the right mix of absurd and mundane, and the tone remains firmly tongue-in-cheek. Like the rest of the Electric Basionland canon, the droll writing makes Canal of Horrors a pleasant reading experience.

But how does it play? You are in luck. I ran this adventure as an intermezzo between a starting adventure in a Bastionland hospital and You Got a Job on the Garbage Barge (a play report, of sorts, is here). However, my problems with the adventure are best illustrated by the changes I made. In Canal of Horrors, the player characters begin at the docks. There is an abandoned luxury yacht. To get paid, the characters need to take the boat through the canals to the Buyer at the intersection of Mocktown and the Central Bog boroughs. The canal itself is forked like a trident, but it is a straight path to the Buyer. I always pay attention when designers break their own rules, and in Electric Bastionland, McDowall provides the following advice about mapping Bastion: “draw two or more circuits denoting different transport routes, ensuring they cross over each other.” There is no circuitry here, and players don’t really need to make any interesting navigational choices to get from the starting point to the end. Essentially, it is a railroad with five locks between start to end, with each lock having a 50% chance of triggering an encounter. So I flipped the adventure geographically (partially as a necessary way of shoehorning in the Garbage Barge), but also provided multiple routes through this section of the city. My players ended up crossing bridges on foot, taking cable cars, and swimming in the canals as they made their way from a privatized hospital north Mocktown to the Dock to the south. The worldbuilding and writing of the adventure drew me in, but the adventure structure itself is lacking (perhaps to be expected, based on the real estate the adventure covers [several city districts] versus its real estate in the book [two aesthetically pleasing pages]). Like many adventures, it takes some tailoring to make Canal of Horrors as flattering as it can be when you bring it to your gaming table.

…

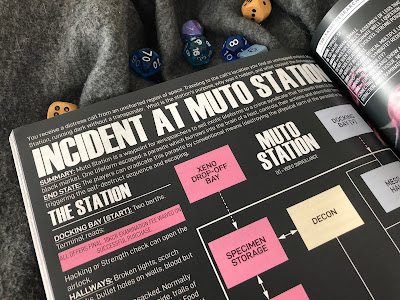

Muto Station (Review by Dan D.)

The Incident at Muto Station is a Mothership adventure by Brian Hauffer, which I ran for three players who had no experience at all with the system to great success. It’s a rather simple setup - here is a creepy, if linear, abandoned space station, there is a horrible monster onboard it - but that's fine for a one-shot. It doesn’t have much in the way of reason to get involved, other than a brief mention of it being a place for poachers to drop off ill-gotten xenos for sale, so when I ran it, I framed it as a cleanup job, grabbing some data and scrubbing the rest under the auspices of a shady patron. Worked like a charm. The monster is big and gribbly and has a table of behaviors and tricks, plus a much-appreciated note that it will start cutting off escape attempts when the players try to leave (as there’s not much stopping them otherwise).

The players had fun, it was easy to run, and that’s fine enough for me.

…

Ghost Ship (Review by

mv)

*

Ghost Ship is a module for Mothership by Matt and Charlie Umland. This 2 page spread promises a paranormal exploration of a long forgotten derelict. “Those who investigate it often never return” - we are warned right off the bat. OoOOooo. Rotate 90 degrees, we got the classic badly kept poster (terrifying), maybe a blueprint - clear yet grungy design by Jonah Nohr (known for Mörk Borg).

**

Ghost(s) / are the main / supernatural / part of this / Ship. Encounters with them are randomly generated, so it took some improvisation to make them fit into the various rooms of the ship. However it was super fun to be surprised by the creepy specters I’ve rolled up. One thing to watch out for are possessions. There are two random table entries that have the ghosts possess PCs and deal harm, and one ghost who possesses to speak. They are not in any way baked in the overall plot of the module, so you can decide with other players if you want to use these entries or not.

***

I ran the module using Ian Yusem’s funnel rules from The Drain. The players used their numbers to split off and explore various rooms simultaneously, which made the session feel like a true haunted house horror flick. Encounters with the ghosts were spooky and memorable, but the turret traps felt a bit out of place when there is such a cool paranormal premise. After the ship was cleared, the players were left with a lot of hooks to follow up on. What’s up with the weird sphere? What to do with the expensive equipment? Where to transport the survivors?

****

10/10 would get haunted by space ghosts again.

...

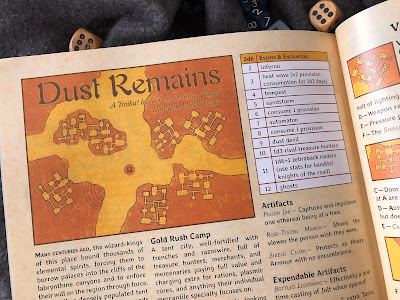

Dust Remains (review by Anne)

A few years ago, I was running a weird west

Dungeon Crawl Classics campaign where I went searching for mine-themed adventures to reskin and convert to

DCC. I used

Melancholies & Mirth’s Abandoned Mines Above the Caverns procedural generator, reskinned

Into the Odd’s Iron Coral as “The Irontown Corral,” and even started in on

Goodberry Monthly’s Goldsoul Mines before my play group moved on to other things. If I had known about

“Dust Remains” at that time, it definitely would have made my list to try, and might have beaten out one of the others.

Christian Kessler pushes the two-page format to probably its absolute limit, giving us a mini-setting on one page and SIX mini dungeons on the other. In the extra space, Christian finds room to give us a table of encounters, four new monsters, a list of ghosts, a random table of minor treasures, and 11 unique magic items and spells, all written up for Troika and other descendants of Fighting Fantasy.

“Dust Remains” presents us with a series of ancient tombs, left over from an empire of cruel wizard kings, carved into the cliff faces of a winding canyon. The area is still haunted by elemental spirits who escaped from their long-ago enslavement, and by the zebra riding nomads who claim to be the empire’s only survivors. Some of these details, along with the names of the tombs - “Vault of Enuliki” or “Vault of Mazzolamus” for example - make me think the setting is meant to be fantasy Africa. There’s a tent city of wannabe tomb robbers and the various merchants and traders that accompany any gold rush, and a second camp of “rich fucks desiring ancient artifacts as status symbols” who provide an immediate market.

The flavor of the various treasures and the activities of the ghosts (which show typical actions of the long-dead imperials) help to communicate the distant culture of the ancient empire. The dungeon keys consist mostly of traps and puzzles, plus a list of treasures behind the final door at the back of each vault. The variety Christian presents is impressive, although the referee will likely want to add a bit more to each dungeon to bring them to life and give them a true sense of exploration. The referee will also need to create NPCs to populate the groups described in the setting introduction. Given all that Christian manages to fit into the available space though, I think these limitations are understandable.

The greatest flaw in “Dust Remains” is the maps, which are almost unreadable. The region contains two different encampments plus all six dungeons. I’m not sure which camp is shown or where the second one is located. The dungeon maps are reproduced in slightly smaller form on the second page, where a handful of the rooms are keyed. At that size, and with the very thin font used on the key, it’s very difficult to make out where anything is supposed to be. Christian’s instructions for randomly stocking any unkeyed rooms also ask the referee to differentiate between “accessible” and “inaccessible” rooms, a distinction I’m not sure I can make quickly at a glance.

If I had a second quibble, it would be that the anticipated time frame of the “Events & Encounters” table isn’t specified and seems unclear. I would guess you’re meant to check daily, because that’s the only way certain results make sense, but others seem a better fit for checking on expedition time.

...

Lair of the Glassmakers (Review by Ava)

I ran Lair of the Glassmakers for a group of 4, mostly new players, using Into the Odd. I selected this particular adventure as I felt the rooms full of inventive, creative puzzles and the adventure themed around cute, mischievous glass kobolds (visually depicted in a pixel art style that reminds one of Pokemon by way of Moomin) would be a good intro for a group of queers who had never played D&D before and were used to the softer fantasy of the new She-Ra cartoon.

I was mistaken. Lair of the Glassmakers is, if run as written, an absolute meat grinder.

The rooms are, as previously mentioned, full of interactive elements and fun puzzles. There’s an alchemy mini-game, and reflections that are alive, and an Annoying Fucking Cat who is literally designed to create hijinks and chaos. This is all really great. If the dungeon was actually just what was keyed within the rooms and nothing else, no denizens, it would actually make for a really fun, if low-stakes, little puzzle-solving session.

The failure of this to all cohere comes in the way random encounters are implemented, and the denizens of this particular dungeon.

The dungeon is the workshop of a glassmaker and alchemist. It is full of treasure, which adventurers will want to ransack. Every room contains, as a random encounter, d6-1 glass kobolds (the entryway to the dungeon, not a keyed location on the map, also has 4 glass kobolds in it). These kobolds surprise on a 2 in 6 (3 in 6 first time they’re encountered) and if they surprise, they each nick an item from the players after which it ends up in the bedroom.

This setup strains credulity for me a little bit already. In the first case, it isn’t quite clear how the stolen items end up in the bedroom. The most logical reading of it is that the kobolds run off with the stolen items to the bedroom but: why? And how does one handle this running off? Do they do it at the beginning of the encounter, absconding in a Road Runner-esque fashion before the PCs have time to react? What if the PCs plan for this and try to catch the kobolds before they run off? And what becomes of these fleeing kobolds? Do they linger in the room next to the bedroom? Do they disappear into the ether? Am I supposed to roll for how many kobolds are in each room each time the players enter any room, or just the once? These might seem like petty questions that any GM worth their salt could make a ruling on, but this sort of nebulous quantum amount of kobolds that always end up teleporting stolen goods into a bedroom strained my credulity, and undermined my sense of this location as a coherent space.

But of course, that only occurs when the kobolds surprise the PCs. The other 67% of the time, what do they do? Well, they guard the place from intruders who want to mess up the workshop or steal from it, and guard its owner Elsa with their lives. No morale rating is given (which feels odd; the module is labelled system agnostic but gives AC values as Plate or Leather and Levels as Thieves or Magic User, so its clearly working with OSR systems in mind), so this seems to imply fanatical glass kobolds that will fight any adventurers to the death. With several of them in every room, confrontations are bloody and frequent. For the low level characters this module is recommended for, this would be a meatgrinder.

The space is small enough (8 rooms all jammed close to each other) that random encounters aren’t really necessary in order to provide a sense of risk to orienteering: it would have been better served with a definite amount of glass kobolds keyed to each room, preferably engaging in distinct but cute hijinks which provide PCs a method of interacting with the kobolds that isn’t wholesale slaughter.

The only other inhabitant of the dungeon, Elsa the glassblower/alchemist, isn’t much better. She hides as an imperceptible glass statue (undetectable without detect magic), and she will only act if she feels the players are messing with her space, in which case she attacks them (dealing 3x damage on a surprise, which she has a 4 in 6 chance of). So this character, potentially the most interesting person to interact with, certainly the only person to parlay with if you want to be friendly with the kobolds, has two states: 1) unable to be interacted with whatsoever or 2) murdering the party. Oh and also she’s in the very first room of the dungeon, so the players will almost certainly be immediately attacked, being drawn into an ambush against a 5HD creature and d6-1 kobolds at the very beginning of the adventure.

Really, with there basically being two types of inhabitants in this dungeon (mook and boss) that are all singularly aligned to common purpose, this can’t really be classified as a dungeon at all. It’s a faction lair, and should be treated as such. The only way to get through it for a party of players is directed assault which requires foreplanning, or placed in relation to other faction lairs so as to allow emergent social play from competing agendas and goals.

...

Dissident Whispers was produced by the Whisper Collective, in coordination with 90 individual collaborators. It is available in Print & PDF for $30 at Tuesday Knight Games (North America), in PDF for $20 at itch.io or DriveThruRPG. Physical copies outside of North America were previously being distributed by Melsonian Arts Council, but as of time of writing that option is no longer available.